- WHAT IF CLINTON WINS ——US President...

- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- The Contexts of and Roads towards t...

- Beyond the Strategic Deterrence Nar...

- America’s 2016 Election Risk, China...

- Three Features in China’s Diplomati...

- Three Features in China’s Diplomati...

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- Identifying and Addressing Major Is...

- Identifying and Addressing Major Is...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- Wuhan 2.0: a Chinese assessment

- The Future of China-India Relations

- Evolution of the Global Climate Gov...

- The Russia-India-China Trio in the ...

- Balancing Leadership in Regional Co...

- Coronavirus Battle in China: Proces...

- China’s Fight Against COVID-19 Epid...

- Revitalize China’s Economy:Winning ...

- International Cooperation for the C...

- Working Together with One Heart: P...

- The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities

- The Tragedy of More Missed Opportun...

- China-U.S. Collaboration --Four cas...

- Competition without Catastrophe : A...

- Lies and Truth About Data Security—...

I. Securitization

Energy is considered a strategic commodity due to its scarcity and geographical concentration. It can be used as a tool to blackmail energy-poor nations, exposing them to a wide range of threats with respect to the extraction, processing and transportation of resources.[①] In the face of these threats, the purpose of energy policy is “to assure adequate, reliable supplies of energy at reasonable prices and in ways that do not jeopardize major national values and objectives.”[②] Consequently, the concept of energy security involves military, economic and geopolitical aspects. Countries that securitize their energy policy aim at self-sufficiency and, if it is not feasible, diversification of resources and sources, strategic reserve build-up and energy conservation and efficiency.[③]

Energy policy involves four primary dimensions: availability refers to geological existence of resources; accessibility refers to the geopolitical elements that influence the supply of oil; affordability refers to the price of oil; and acceptability refers to environmental and societal costs of energy.[④] States come under the influence of these factors in varying degrees depending on their level of industrial development, domestic policy, geographical location and international political conditions. If these dimensions are regulated and overseen exclusively by the state, energy policy is securitized. In this case, certain diplomatic, economic, and, at times, military instruments are utilized to ensure a steady and safe flow of energy. It must be underlined that these four dynamics as drawn from the literature on energy security are not fully agreed upon.[⑤] All in all, however, from whichever point of view one may look at it, securitization requires that the state provide safe and affordable energy resources to assist national economic and political objectives.[⑥]

II. China and India: Share of Oil in the Energy Mix and Resource Diversification

China and India’s national energy mixes differ considerably but the two countries share certain characteristics in terms of their approach to energy policy. Perhaps the most common strategy is resource diversification which aims to reduce dependency on foreign supplies by increasing indigenous production. Historically, the largest increase in China’s primary energy supply was seen in the production of coal and crude oil. Other resources such as natural gas, nuclear and renewables registered much smaller increases, although over the past ten years their share also began to increase. Nonetheless, growth in the production of non-fossil resources still lags behind the increase in overall energy consumption.[⑦] Therefore, oil (as well as coal and natural gas) continues to weigh heavily in China’s total energy mix.

In 2011, oil constituted 18% of China’s total energy use, the second largest resource after coal (69%), while hydro power (4%), natural gas (4%), nuclear (1%) and other renewables (1%) accounted for much less in total consumption.[⑧] According to estimations, as of percentage, the share of oil in China’s total energy mix will not increase from the present levels thanks to growth in the acquisition of other resources; however, the amount of oil consumed will continue to increase as the overall demand grows.

Similarly, India’s energy basket has been a mix of all the resources available, including renewables. Over 70% of India’s energy consumption is based on fossil fuels, with coal accounting for 41%, followed by crude oil and natural gas at 23% and 8%, respectively. As of percentage of share in total energy mix, crude oil accounts for a greater space in India than it does in China. However, as will be seen in the next section, China’s net consumption of oil (as well as nuclear and natural gas) is still much larger than that of India. This is explained by the difference between the scale of the two economies and thus by the consumption per capita.

Although India is the world’s fourth largest consumer and a major producer of energy, coal occupies a much smaller space in India’s energy basket than China’s and the difference in the use of coal is largely compensated by biomass and other waste. Hydroelectric, however, seems to play a less significant role in India’s energy mix even though the country was the world’s 7th largest producer of hydroelectric power in 2010.[⑨] Nonetheless, the dominance of coal in the mix is likely to continue in the foreseeable future. The U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) predicts that the share of coal and petroleum is going to be about 66.8% in total commercial energy produced and about 56.9% in total commercial energy supply by 2021-22. The share of crude oil in production and consumption is expected to be 6.7% and 23%, respectively, by 2021-22.

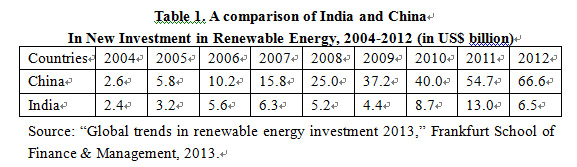

In response to the growing dependency on coal and import of oil and natural gas, China has begun to invest in alternative energy resources such as wind and solar as part of its resource diversification scheme. Accordingly, in 2012, it became the world’s top destination for green energy investments, spending over $60 billion in solar, wind, and other renewables.[⑩] Currently China ranks first in terms of installed wind power and hydropower capacity and the largest manufacturer of solar photovoltaic cells, commanding a 30% global market share.[11] However, China obtains only about 9% of its total primary energy from non-fossil resources even though it seeks to increase that share to at least 11.4 % by 2015 and 15% by 2020.[12] The growth in the share of renewables will be largely offset by the decrease in the use of coal for electricity generation, hence will have little impact on the demand for other hydrocarbon resources, especially for oil. Accordingly, it is estimated that coal-fired power generation capacity will decline from 67% in 2012 to 44% in 2030 even though in absolute terms it will continue to grow.[13]

Under similar energy pressure as in China, policy-makers in India proposed alternatives and revisions to the national energy strategy. In response to import dependence, the Indian government aims to reduce vulnerability by increasing domestic production of oil and alternative resources. India is rich in natural resources and strives to explore its oil and gas fields, as well as develop new capacities of renewable energy power plants. Exempli gratia, India encourages consumption of clean energy by raising production and import of natural gas. It aims to stimulate the development of renewable sources of energy as well, including offering incentives to increase the use of nuclear energy, wind power and solar energy. The Indian government has also proposed the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme, the main goal of which is to promote energy efficiency among energy-intensive industries and the electricity sector by using market-based mechanisms.

The Indian government and the private sector have recently begun to invest in renewable resources and drafted a plan to build national electricity grid to carry power from wind and solar plants.[14] In addition to solar and wind power, India has various projects to enhance energy production and secure supplies to urban and rural populations, one of which being nuclear energy. Thanks to extensive research and expertise, India has developed a thorium-based nuclear reactor that is considered a “future fuel.”[15] Similarly, China has an ambitious nuclear-generation programme, planning to generate almost 60 gigawatts of energy by 2020.[16] Overall, India lags far behind China in terms of investment in alternative energy resources: in 2012, for example, China’s investment in alternative energy resources was ten times larger than that of India.

III. Production, Consumption and Dependency

Currently the world’s second largest economy in GDP and the largest in manufacturing, China has grown increasingly dependent on foreign energy sources over the past two decades. Even though it owns massive resources, including oil fields, China’s oil reserves, the highest in the Asia-Pacific region, are mostly located in the country’s northeast regions. About 85% of China’s oil capacity is located in interior regions, most of which are mature reserves that have been exploited for a long time.[17] Among those, the most important are the Tarim basin (the largest inland basin in China) in Xinjiang and the Daqing in China’s northeast region.[18] In 2012, China’s proven oil reserves stood at 20.4 billion barrels, an increase of 4 billion barrels from three years ago.

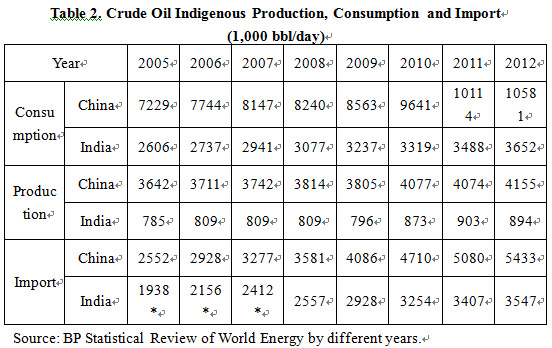

Currently, China is the largest energy consumer in the world and the second largest consumer of oil after the U.S. China’s daily consumption surged beyond the 10mb/d threshold in December in 2012, reaching 10.6mb/d.[19] In 2013, the country used 10.7 mb/d of oil, an almost 4% increase from 2012, accounting for one-third of the world’s oil consumption growth in 2013.[20] There is little prospect for a reversal of this trend in the foreseeable future: by 2035, China’s national consumption is expected to rise to 15 mb/d and its net oil import will account for more than 80% of its total oil consumption.[21]

While China’s oil consumption has grown exponentially, production stalled after an initial jump. Over the years, the ratio of the country’s import to domestic production has changed dramatically. In 1965, oil production stood at 0.2mb/d, which then jumped to 2.8mb/d in 1993. From 1997 (3.2mb/d) onwards, however, domestic production lost steam, and stabilized at around 4.3mb/d in 2011, registering a net production-consumption ratio of -4.1mb/d. It is estimated that China’s production will rise to about 4.6 mb/d by the end of 2014. In order to satisfy its oil needs, the PRC doubled its import in the 2005-2012 period. Accordingly, in the fourth quarter of 2013, China became the largest global net importer of oil. EIA estimates that China will surpass the United States in net annual oil imports by the end of 2014.[22]

Although on a lesser scale than China, growth in India’s oil consumption has also largely been the result of rapid industrial development, urbanization and increase in transportation. Currently, India is the fourth largest energy consumer in the world after the U.S., China, and Russia. In 2011, India was the fourth largest consumer of oil and petroleum products, following the United States, China, and Japan. Accordingly, whereas its production of crude oil increased only incrementally over the past ten years, consumption achieved a continuously upward momentum, although, still, the scale has been smaller than half of China.

Indian oil reserves in commercial quantities were first discovered in Assam in 1889. Then later Oil and Natural Gas Commission discovered oil in Gujarat in 1959 and opened other fields in the 1960s and 1970s. According to the Oil & Gas Journal, India had 5.5 billion barrels of proved oil reserves at the end of 2012. About 53% of the reserves come from onshore resources, while 47% are offshore reserves, most of which are found in the western part of India, particularly western offshore, Gujarat, and Rajasthan. The Assam-Arakan basin in the northeast part of the country is also an important oil-producing region and contains more than 10% of the country’s reserves.[23]

Currently India operates a number of gas and oil fields in various parts of the country, although production comprises no more than 30% of its consumption. Crude oil production has remained in the range of 0.8 to 0.9 mb/d since 2005-2006 with year to year variations. Starting from 2009-2010, production slightly increased and reached 0.9 mb/d. In contrast to indigenous production, India’s import of oil grew significantly between 2005 and 2012. In 2005 import amounted to 1.9 mb/d and in 2010 reached 3.3 mb/d while production increased only from 0.8 mb/d to 1.0 mb/d during 2005-2013.

As some observers note, India may face a serious energy crisis as dependence on imports will double by 2031-32 from about 25% in 2003-2004.[24] And oil dependence in particular is expected to go up to 90% by 2025, much higher than that of China as a percentage of national consumption.[25] Thus it becomes clear that the only short and medium-term option available for India, as for China, has been source diversification. Over the years, both countries have embarked on ambitious going-abroad strategies, attempting to utilize effectively the available political and economic instruments in an effort to ease the vulnerabilities of heavy reliance on the Middle East as a source of energy.

IV. Oil Dependency and Source Diversification

According to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2012, the past ten years saw a huge shift among the world’s leading energy consuming economies. In 2000, China was the world’s third largest energy user, taking up 10.8% of global consumption, superseded by the EU (18.4%) and, by a wide margin, the U.S. (24.7%). In 2011, China rose to the top spot with a 21.3% share of the world’s total energy consumption. During the same period, the EU’s share of consumption fell to 13.8% and the U.S., to 18.5%.[26]

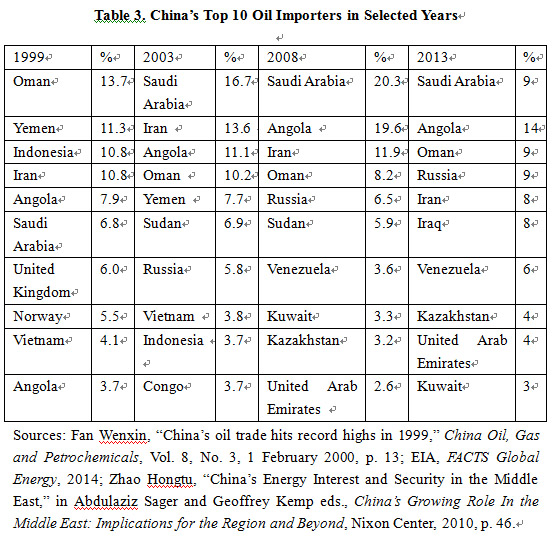

Thus China’s growing energy consumption and declining production-consumption ratio require the country to seek energy resources (mainly oil and natural gas) overseas. Although Beijing has worked to diversify its energy sources in recent years, the Middle East, where 64% of world’s proven oil reserves are located, is still the largest source of import. Currently, China’s oil dependency on the Middle East stands at about 55% of its total import. In 2011, China purchased 2.9 mb/d of oil (a 15% increase over the previous year), which accounted for 60% of its oil imports.[27]

China is currently the largest energy importer from the Gulf.[28] By country, Saudi Arabia is Beijing’s largest import source of crude oil. In 2013 Riyadh accounted for nearly 20% of the country’s total demand, followed by Angola (14%), Russia (9%), Iran (8%), Oman (9%), Iraq (8%), Venezuela (6%), Kazakhstan (4%) and the UAE (45).[29] Accordingly, of the top ten sources of crude oil in 2013, six were from the Middle East, which accounted more than half of China’s import. It is projected that dependency on the oil from the Middle East will grow to 80% of China’s total demand in less than two decades.[30] Consequently, China’s oil supply balance is going to remain negative in the following decades since neither domestic nor regional production satisfies its ever increasing demand for hydrocarbon resources.[31]

In response to over-dependency on the Middle East, China has sought source diversification. One major strategy has been to build international pipelines to transport crude oil (and natural gas) from neighboring countries. To this end Chinese National Oil Companies (NOCs) have invested heavily in transnational pipelines to diversify the country’s energy supply, distribute risks involved in sea-based transportation and decrease dependency on the Middle East. Since the early 2000s, the PRC has secured agreements with neighboring countries to import oil and gas from almost all directions. On the north, oil import from Russia has increased with China’s inclusion into the ESPO project. From the west, the oil pipeline from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and the gas pipeline from Turkmenistan bring energy into China’s Xinjiang region. And from the south, the Sino-Burmese Gas and Oil Pipeline provides China with access to Myanmar’s natural gas reserves. Thus overland routes serve as important instruments to aid China’s source diversification strategy.[32]

Another example in Chinese diversification strategy is active energy diplomacy in Latin America.[33] Since the early 1990s, Beijing has made substantial investments in the region. Especially the spread of nationalization movement in the 2000s allowed China to engage in loan-for-oil deals and mergers and acquisitions. Today China conducts energy business across the continent, with Venezuela, Brazil and Ecuador accounting for nearly 80% of Beijing’s oil-related projects in Latin America. But still, the region’s share in China’s import has not grown considerably. In 2010, Latin America accounted for only 8.6% of its total import.[34]

Although it is expected that China’s energy relations with the rest of the world is going to expand further, the weight of the Middle East in the larger energy picture is obvious. Even if renewables, increased efficiency standards and source and resource diversification may continue to contribute increasingly to China’s energy mix and usage of oil, taken alone, they will not suffice to meet the growth in demand. Indeed, the major driver for consumption will increasingly be the new affluent middle class that tend to consume more resources. Therefore, energy dependency in the Middle East will continue to constitute a major aspect of China’s international diplomacy. The ways and means in which China chooses to implement this diplomacy will in turn have important regional and global implications.

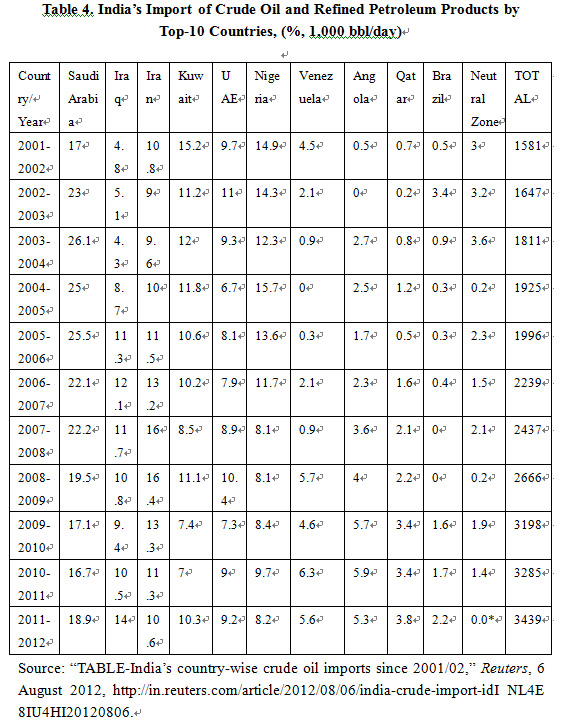

Like China, India’s import of crude oil has followed an upward trend over the past years and currently India is the fourth-largest buyer of crude oil and petroleum products. By 2025 India is expected to overtake Japan as the world’s third-biggest importer. The Middle East has always been a principal region-provider, and its significance has kept growing year after year. In 2011-2012, the Middle East’s share in India’s total import comprised approximately 70% of its total crude acquisitions. In this respect, India’s dependency on the region, as a percentage of its overall imports, is larger than that of China. In 2011-12, India’s overall import roseby 4.7%, with Saudi Arabia (19%), Iraq (14%), and Iran (11%) as its main suppliers. Among the top ten partners, the share of countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, and Qatar has been stable for the decade, while the share of Iraq and Kuwait has seen some changes.

Due to high dependency on Middle Eastern oil and recent political uprisings in the region, India has also been seeking source diversification, and, owing to its favorable geographical location, the best choice appears to be the African continent which accounts for 20% of India’s oil imports. Indeed, Indian oil companies have invested heavily in equity assets in Sudan, Ivory Coast, Libya, Egypt, Nigeria, Gabon and Angola. India completed a $200 million project to lay a pipeline from Khartoum to Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Indian companies have also invested in exploration and production blocks in Madagascar and Nigeria.[35] Furthermore, in order to reduce dependency on the Middle East, India’s private-owned companies have increased purchases from Latin America.

However, very much like China, share of the regions other than the Middle East in India’s oil imports has not significantly changed during the last decade. The main problem has been instability in most African countries. For example, civil wars in Sudan forced India’s national oil company OVL to shut down all projects in the country and total energy production dropped by over a third in the last three years.[36] In order to diversify its supplies and secure oil imports India has approached Canada[37] and Central Asian countries for long-term partnership on energy. Nevertheless, it is estimated that India’s heavy reliance on the Middle East will continue for the foreseeable future not the least because of the region’s dominance in global oil production and its export capacity.

V. China and India’s Oil Diplomacy in the Middle East

It is understood that China’s oil security arises from a structural contradiction between the rising demand for clean-burning (non-coal) and safe (non-nuclear) resources and the significant domestic shortage. Hence, the central objective of the Chinese energy security policy is to address this contradiction with the least possible internal and external consequences. Internal factors, in this regard, inform external factors. Internally, the government needs to provide adequate amount of energy at reasonable prices whereas, externally, it needs to maintain positive international cooperation while executing bilateral energy diplomacy based on the going-abroad strategy.

The strategic goal of China’s energy security policy is to obtain adequate, stable and diversified oil supply at a reasonable price. It follows that in no other region have China’s efforts to enable security in energy come under greater pressure than in the Middle East. Because of the complicated geopolitical situation of the region and the level of great power involvement, China has faced many difficulties such as separating its trade in energy from nuclear proliferation activities, engaging the resource-rich countries with questionable human rights records, ensuring security of the sea lanes through which the majority of China’s energy imports move, and protecting its energy-related investments such as oil and gas development and exploitation structures.[38] Other factors for securitization are “the possibility of temporary oil shortage and/or oil price volatility in the international market, natural disaster, uncompetitiveness of Chinese oil firms, and the absence of a crisis management system for oil security.”[39] For these reasons, energy policy remains securitized, involving both hard (military) and soft (macroeconomics) power supported by domestic measures such as energy preservation and diversification.[40]

A similar observation can be made of India. It also faces domestic problems connected with rapid economic development and energy shortages in urban and rural areas. In order to resolve existing problems New Delhi strives to secure its energy supplies by any means possible and fulfill its domestic strategy of increasing indigenous production. The Middle East, in this respect, is the most important region that elicits special attention, as mentioned above, because of numerous internal problems and great power involvement. Thus India seeks its own niche among great powers in order to achieve national goals. In a similar line with China, India prioritizes relations with Middle Eastern countries by pursuing pragmatic diplomacy and building long-term partnerships with all countries, including ‘troublemakers’ like Iran and Sudan, thereby arousing general discontent from the Western governments. Thus the dilemma India faces today involves the question of whether to side with the norm-making powers of the world and follow their neo-liberal values or to pragmatically pursue its own interests to accomplish sustainable economic development.

It is obvious that, on par with the strategic importance of the Middle East for their national economic development, both China and India securitize their energy policy. Driven by growing consumption and inadequate domestic production (albeit in varying degrees), both governments use similar approaches to energy, which include building long-term partnerships in the region through bilateral agreements. NOCs play a great strategic role for China and India in their attempt to strike investment and joint exploration and development agreements with the countries in the Middle East. Similarly, securitization exposes them to larger geopolitical conditions and often the lines between the various levels of national energy diplomacy (economic, political, cultural, etc.) are blurred.

Beijing has moved from low politics (market-approach) to high politics (security approach) in energy over the years. As its dependency on foreign energy resources deepened, China took certain steps from the mid-1990s onwards. First of all, it went on to diversify domestic energy resources. For that purpose, it focused on the expansion of natural gas production and invested heavily in the renewables. Second, Beijing began to internationalize national energy industry. Chinese NOCs signed a number of bilateral deals with countries in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Finally, it engaged in extensive inland activities, initiating five overland pipeline projects from the year 2006 with Russia, Myanmar, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Thus, understood as the active involvement of the central government in foreign energy transactions in an effort to achieve certain national goals, including enhancing energy security and realizing sustainable economic growth, oil diplomacy continues to be the mainstay of China’s energy strategy.

Recognizing the importance of integrated political approach to overseas oil strategy, New Delhi pursues energy diplomacy that consists of substantial, pro-active, multifaceted engagements across the world. These engagements are aimed at achieving the following: First, significant enhancement of domestic resources and capabilities by bringing in new foreign technologies and expanding the national knowledge base. Second, going-out strategy which includes acquisition of assets abroad (both onshore and offshore) through equity participation in producing fields and/or exploration and production (E&P) contracts in different parts of the world. Third, participation in downstream projects (refineries and petrochemicals) in producer and consumer countries on the basis of criss-cross investments. Fourth, setting up transitional gas pipelines although currently India does not have any transnational oil pipelines. And finally, obtaining technologies to promote sustainable energy use, including conservation and increased use of environment-friendly fuels.[41]

China and India’s securitization of energy policy in the Middle East is closely related to their changing energy prospects. For Beijing, the region’s complicated geopolitical situation and intense great power involvement lead to numerous challenges such as ensuring security of the sea routes, guarding against political crises and civil wars in energy producing nations, and protecting its energy-related investments from non-state threats.[42] In response to the challenges, Beijing has set out to negotiate with the oil producing countries on bilateral basis without seeking alignment with international institutions such as the IEA or OECD. Chinese policymakers remain concerned as to the issues of access, exploration and transportation as industrial development and income growth push the nation into the global energy market. Hence, considering energy one of the strategic components in China’s national security, the PRC has utilized tools that brought the state to the forefront of the nation’s energy policy.[43]

In order to ensure a steady and secure flow of energy from its supplies, India, too, has begun to pursue active bilateral diplomacy that includes, among others, establishing close political relations with Middle Eastern states and signing economic, defense and security agreements. These policy measures have unavoidably placed the state at the center of energy diplomacy. As the geopolitical situation evolves and changes quickly in the Middle East, Indian policy of engaging each country and not picking sides in any international conflict does not satisfy all participants and, like China, at times, India finds itself caught in regional crises.[44]

The most strategic component of China and India’s securitization of energy policy is the going-out policy. From the Chinese perspective, in general terms, going-out involves: (1) securing access to energy supply through investment in upstream projects; (2) signing equity oil agreements with foreign NOCs to enable long-term, stable access to energy resources; (3) taking oil off the market; and (4) engaging in world-wide search for oil.[45] It is observed that India learns from Beijing and, using the going-abroad strategy, exercises various diplomatic means to enhance relations with main oil exporters by not only providing economic benefits to these countries, but also assisting in maintaining the extant regimes. It, for example, searches for lowering oil prices and thus strengthens relations with the states ostracized from the larger international community to gain benefits from unfavorable geopolitical environment. National interests, in this case, are represented by state-owned companies, rather than private oil corporations.

Perhaps the most effective going-abroad strategy China utilizes is equity-oil agreements which help secure and diversify energy sources, increase expertise in unconventional oil exploration techniques, and capture value upstream.[46] The global financial crisis and China’s vast foreign exchange reserves have so far enabled Beijing to buy equity in existing oil projects or acquire stakes in energy companies with investments in highly profitable areas. According to the EIA, since 2009, “the NOCs have purchased assets in the Middle East, North America, Latin America, Africa, and Asia.”[47] In 2011, Chinese NOCs invested $12 billion in gas and oil, which accounted for over 60% of the global equity oil purchases. Historically, China’s overseas equity production grew from a mere 140,000 b/d in 2000 to 1.5 mb/d in 2011.[48] Since 2008, China’s bilateral oil-for-deals have amounted to $100 billion.[49]

India, too, strives to utilize its national NOCs as part of national energy diplomacy. For example, the state-owned company, ONGC Videsh Ltd (OVL), has begun to acquire energy assets around the world. It has already spent over $10 billion to acquire over three dozen assets in 18 countries. Currently, OVL produces hydrocarbons from its nine assets in Russia, Syria, Vietnam, Colombia, Sudan, Venezuela and Brazil, acquiring 8.87 million metric tonnes of oil and oil equivalent gas in 2009–10.[50] In the Middle East, OVL has initiated exploration projects in Iraq and Syria. Nevertheless, as some experts observe, OVL’s performance is not efficient, especially in comparison with China’s state-owned companies such as China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and CNOOC.[51] It is observed that Chinese oil companies enjoy more autonomy in decision-making than their Indian counterparts. Often Chinese NOCs act more like profit-oriented entities, which gives them greater flexibility and efficiency. Contrarily, Indian NOCs are more dependent on the central government for decision-making, which slows them down and negatively impacts on their competitiveness in the international market. Thus, recently private refinery companies have joined NOCs to achieve greater accessibility to resources.

All in all, China and India securitize energy mainly because of the twin issues of availability and accessibility.[52] To some degree, both nations face a potentially precarious international environment in the region that is composed of relatively weak and unstable states and try to formulate long-term strategies to secure energy supplies. That said, geopolitical risks are often accompanied by certain opportunities. For example, countries such as Iran, Syria and Sudan, which have been exposed to crippling Western sanctions, find China and India eager to collaborate to protect their supplies and reduce international competition with other U.S., European or Japanese energy companies.[53] The result of these policies has yet to be seen. Nevertheless the problems the two countries face are real and both come under different geopolitical forces when they set out to mobilize the optimum strategy. The common outcome of these factors is that both countries’ energy policy is securitized. In the next section, we analyze these divergent factors and assess the most important aspects of securitization in order to present a full picture of China and India’s energy policy in the Middle East.

VI. China and India: Geography and Energy Strategy

We observe that geography is one of the most crucial components that affect China and India’s energy prospects and their respective outlook on energy security. In other words, both China and India appear to have a more or less similar approach to energy (as seen in their securitization strategy) but the two differ radically in terms of their geographic fortunes as well as their success in capitalizing on the existing advantages and in developing policies to counter and control the disadvantages. Generally speaking, India’s geographic location offers a clear advantage over China because of its relatively closer proximity to the Middle East. In this case, India does not have to worry too much about a Malacca Dilemma or piracy off the coast of Somalia. Furthermore, proximity to Middle Eastern oil may allow India to negotiate for better prices and reduce transportation and security costs. However, on the negative side, affordable prices seem to have kept India from seeking a more aggressive source diversification. India’s geographic isolation from the energy centers of Central Asia and Russia locks it into an untenable position with an exclusive dependence on the Middle East. This explains India’s failure in source diversification through effective pipeline diplomacy.

China, on the other hand, is geographically distant from the Middle East and has to rely on extensive SLOCs for its energy imports as the crude oil has to be shipped through a number of critical chokepoints where Beijing enjoys little naval control. This not only increases transportation costs, but also adds to the existing traditional and non-traditional security threats. However, China’s close proximity to Russia and other energy-rich Central Asian republics allows it to engage in source diversification more successfully than India. As Beijing’s active pipeline diplomacy demonstrates, China holds a greater advantage over India in terms of diversification between regions thanks largely to its favorable geographic location. Geography, therefore, may explain China’s more ambitious source diversification strategy which, unlike India, now includes four major overland oil pipelines. In comparison, India seems less advantageous because of its limited geographic exposure to the energy-rich Central Asia and Russia, which constrains its options for source diversification between regions. Viewed from either perspective, geography appears to be a major determinant for the two countries’ securitization of energy policy in their attempt for source and resource diversification.

More specifically, geography shapes China’s energy strategy to a great extent as it relates directly to the transportation of crude oil and natural gas from overseas suppliers to the Chinese homeland. Maritime security, in this regard, is one of the most important drivers for the securitization of China’s energy policy.[54] For most of the oil purchased from the region has to be transported via strategic shipping lanes such as the Strait of Hormuz, the Suez Canal and the Malacca Strait with little Chinese naval presence, Beijing attempts to develop extensive policies to safeguard the critical sea lanes and chokepoints.

Chokepoints are narrow channels located along the most widely used sea routes. Among seven oil transit passageways, the Gulf of Hormuz and the Malacca Strait are the busiest with the highest volume of daily oil flow. In 2009, for example, 15.5 and 13.6 million b/d oil was transported via the Hormuz (17% of oil traded worldwide) and Malacca Straits (14% of oil traded worldwide), respectively. Both sea routes are enormously crucial for China’s energy security prospects because they constitute a great portion of its seaborne imported energy supply.[55] For this reason, in addition to naval modernization, China is working to set up bases along the sea lanes from the Gulf of Hormuz to Malacca Strait that altogether compose a string of pearls.[56]

Apart from the potential threats to the flow of oil from countries with physical control over the chokepoints, the weak presence of the Chinese Navy on the sea routes from the Persian Gulf to Malacca and Taiwan Straits reinforces Beijing’s energy concerns. In the Strait of Hormuz, the stand-off between Tehran and Washington endangered the flow of trade goods and commodities. Numerous times, Iran threatened to close down the Strait if it is attacked by the U.S. and its allies. Although relations between Tehran and the West seem to bottom out, a total rapprochement is nowhere to be seen. Also, in the Strait of Malacca, piracy continues to be a major issue. Hence the modernization of the Chinese Navy and its increasing capability to project power is in large part a response to the country’s distance from the most strategic center of global oil production.[57]

To be sure, its geographical proximity to the Middle East does not entirely save India from many troubles that haunt China. As mentioned earlier, as much as 70% of India’s oil imports come from the Middle East and North Africa. A large portion of the imported oil passes through the Strait of Hormuz and Suez Canal. Thus, India relies heavily on the maritime routes from the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean. Besides, the Middle East itself has often been unstable due to political uprisings and internal and intraregional conflicts as well as long-lasting civil wars. In this regard, India finds it necessary to secure the most important chokepoints and diversify its sources of supply. However, India is still at the more advantageous position than China, because it has a shorter, thus securer, maritime access to Middle Eastern oil.

Consequently, India is highly dependent on maritime oil trade and has a potential to further develop its coastal areas, but it encounters numerous obstacles to connect its northern regions to both energy-rich Middle East and Central Asia. With respect to overland access to energy from north, the main problem India faces lies in neighboring countries – Pakistan and Afghanistan – whose domestic instability and frequent insurgencies create many tensions within India’s territory and hamper the efforts to build overland energy routes and develop feasible energy programs to the full extent. Therefore, geography and politics keep India from source diversification through overland routes. On a positive note, however, the Indian government has recently been active to deepen energy connections with Central Asia and the Middle East. For this purpose the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) might provide the necessary institutional mechanism for multilateral negotiations.

VII. Conclusion

Energy security is a dynamic concept and involves uncertainties and risks due to its wider international context and multilateral nature. This interaction often includes geopolitics as well as economics. In fact, it is safe to say that trade in energy is inherently a geopolitical transaction no matter how big a role economic interests may play. It is geographic, first, because of the geological nature of the commodity itself which is found arrested in underground reserves, and second, because of the need to transport energy in large amounts through maritime and/or overland routes. It is political since, although most of the transactions are done through international institutions and market mechanisms, energy security is exclusively a state affair. The strategic importance of oil for national economic development and the unequal distribution of it across regions add to the risks and uncertainties. Countries could invest and dedicate significant national wealth and manpower on the research and production of advanced military technologies when they are not available on the global market, but, if lacked domestically, hydrocarbon resources have to be found and brought home from elsewhere as it cannot be substituted otherwise.

This research has found that China and India’s energy prospects in the Middle East have commonalities and differences: they are similar in terms of energy dependency on the Middle East and securitization. However, due to their geographical position vis-à-vis the Middle East, the two countries are subject to diverse geopolitical dynamics. It follows that China and India differ with respect to their success in managing and responding to existing geographical advantages and disadvantages. In this respect, China appears to have been so far better adapted to the geographical reality. For example, Beijing has been more successful in source diversification, especially in pipeline diplomacy. As we have pointed out, India’s geographical location is less promising in terms of overland source diversification, thus India is expected to capitalize on its maritime advantages. For example, India is closer to energy-rich Middle East and Africa and can further develop its maritime energy trade. However, so far, New Delhi has not fully explored its geographical potential. All in all, it is expected that the Middle East will continue to occupy a central place in the two countries’ energy diplomacy. And their endeavors to respond to the challenges and to capitalize on the advantages will largely determine the outcomes of their energy security strategy.

Source of documents: Global Review

more details:

[①] Christian Constantin, “China’s Conception of Energy Security: Sources and International Impacts,” University of British Colombia, Working Paper 43, March 2005, p. 3.

[②] Daniel Yergin, “Energy security in the 1990s,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 67, No. 1. 1988, pp. 110–132.

[③] Wu Lei and Liu Xuejun, “China or the United States: Which Threatens Energy Security?” OPEC Review, 2007.

[④] Bert Kruyt, D. P. van Vuuren, H. J. M. deVries and H. Groenenberg. “Indicators for Energy Security,” Energy Policy, Vol. 37, 2009, p. 2167.

[⑤] Benjamin K. Sovacool, “Evaluating Energy Security in the Asia Pacific: Towards a More Comprehensive Approach,” Energy Policy, Vol. 39, 2011, pp. 7473-7478.

[⑥] William Nuttall and Devon Manz, “A New Energy Security Paradigm for the Twenty-First Century,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 75, No. 8, 2008, p. 1250; United Nations Development Program, World Energy Assessment: Energy, the Challenge of Sustainability, New York: United Nations, 2000.

[⑦] “Non-Fossil Fuels Rise in China’s Energy Mix – Paper,” Reuters, January 14, 2014, http://uk. reuters.com/article/2014/01/14/china-energy-idUKL3N0KO1FA20140114.

[⑧] Energy Information Administration, “Country Brief: China,” Last Updated, February 2014, http://www.eia.gov/countries/analysisbriefs/China/china.pdf.

[⑨] Energy Information Administration, “Country Brief: India,” Last Updated March 18, 2013, http://www.eia.gov/countries/analysisbriefs/India/india.pdf.

[⑩] “China Is #1 In Renewable Energy Investment, US #2, Japan #3 (CHART),” Cleantechnica, April 5, 2014, http://cleantechnica.com/2014/04/05/china-1-renewable-energy-investment-us- 2-japan-3-chart/.

[11] Renewables Global Status Report: 2013 Update, Paris: REN21 Secretariat, http://www.ren21. net/REN21Activities/GlobalStatusReport.aspx.

[12] “Renewable Energy In China: An Overview,” The Network for Climate and Energy Information, May 13, 2014, http://www.chinafaqs.org/files/chinainfo/ChinaFAQs_Renewable_Energy_ Overview_0.pdf.

[13] “The Future of China’s Power Sector: From Centralized and Coal Powered to Distributed and Renewable?” Bloomberg New Energy Finance, August 2013, http://about.bnef.com/white-papers /the-future-of-chinas-power-sector/.

[14] Archana Chaudhary, “India Plans to Spend 6 Billion Euros on Wind, Solar Transmission,” Bloomberg, August 14, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-08-14/india-plans-to-spend- 6-billion-euros-on-wind-solar-transmission.html

[15] Virendrasingh Ghunawat, “Advanced Heavy Water Reactor is the Latest Indian Design for a Next-Generation Nuclear Reactor that Will Burn Thorium as Its Fuel,” India Today, February 27, 2014, http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/advanced-heavy-water-reactor-ahwr-thorium-reactor- bhabha-atomic-research-centre-mumbai-india/1/345888.html.

[16] Jennifer Duggan, “China Working on Uranium-Free Nuclear Plants in Attempt to Combat Smog,” The Guardian, March 19, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/19/ china-uranium-nuclear-plants-smog-thorium.

[17] Energy Information Administration, “Country Brief: China,” Last Updated February 2014, http://www.eia.gov/countries/analysisbriefs/China/china.pdf.

[18] For an extensive review of China’s on-shore and off-shore sites, visit http://www.oilchina.com/ eng/Service-Center/oilfields.htm and http://www.oilchina.com/eng/Service-Center/oilfileds/ bohai.htm.

[19] Kenneth Rapoza, “China Wants More Oil,” Forbes, February 2013, http://www.forbes.com/ sites/kenrapoza/2013/02/18/china-wants-more-oil.

[20] Energy Information Administration, “Country Brief: China”.

[21] International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2012, http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/.

[22] Energy Information Administration, “Country Brief: China”.

[23] Energy Information Administration, “Country Brief: India”.

[24] Eric Yep,” India’s Widening Energy Deficit,” Wall Street Journal, March 9, 2011, http://blogs.wsj.com/indiarealtime/2011/03/09/indias-widening-energy-deficit/.

[25] Bhupendra Kumar Singh, “India’s Energy Security: Challenges and Opportunities,” Strategic Analysis, Vol. 34, No. 6, November 2010, p. 799.

[26] See, British Petroleum, BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2012, http://www.bp.com/ content/dam/bp/pdf/Statistical-Review-2012/statistical_review_of_world_energy_2012.pdf.

[26] International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook, 2011.

[27] Xiaojie Xu, “China and the Middle East: Cross-Investment in the Energy Sector,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 7, No. 3, June 2000, p. 9.

[28] Grace Ng, “China Inching Towards Bigger Role in Persian Gulf,” Straits Times Indonesia, January 28, 2012, http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/archive/china-inching-towards-bigger-role- in-persian-gulf/.

[29] International Energy Agency. “Country Analysis Briefs: China,” September 2012, Revised April 2013.

[30] See the full report here, British Petroleum (BP), BP Energy Outlook 2030, 2013, http://www.bp. com/content/dam/bp/pdf/statistical-review/EnergyOutlook2030/BP_Energy_Outlook_2030_Booklet_2013.pdf.

[31] “Energy Outlook for China,” KPMG, 2005, http://www.kpmg.com.cn/en/virtual_library/ Industrial_markets/Energy_outlook.pdf.

[32] Lei Wu, “The Oil Politics & Geopolitical Risks with China “Going out” Strategy toward the Greater Middle East,” Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (in Asia), Vol. 6, No. 3, 2012.

[33] Jorge Blázquez and José María Martín-Moreno, Emerging Economies and the New Energy Security Agenda, Real Instituto Elcano, April 27, 2012.

[34] Hongbo Sun, “The dragon’s oil politics in Latin America,” The Focus: Chinese and EU Energy Security, No. 62, Winter 2012.

[35] Fantu Cheru and Cyril Obi, “India – Africa Relations in the 21st Century – Analysis,” Eurasia Review, September 19, 2011.

[36] Luke Patey, “No Oil in Troubled Waters,” The Hindu, March 25, 2014, http://www.thehindu businessline.com/opinion/no-oil-in-troubled-waters/article5831115.ece.

[37] “India Keen on Buying Oil, LNG from Canada on Long-term Basis,” The Economic Times, January 13, 2014, http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-01-13/news/46150039_1_ indian-oil-corp-gail-india-oil-sources.

[38] Lei Wu, “The Oil Politics & Geopolitical Risks with China “Going out” Strategy toward the Greater Middle East,” pp. 58-61.

[39] Shaofeng Chen, “Motivations behind China’s Foreign Oil Quest: A Perspective from the Chinese Government and the Oil Companies,” Journal of Chinese Political Science, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2008, pp. 83-88.

[40] Jian Zhang, “China’s Energy Security: Prospects, Challenges, and Opportunities,” The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies, 2011, p. 2.

[41] Talmiz Ahmad, “Energy Security and India’s Diplomatic Effort,” RITES Journal, January 2011, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/energy security.pdf.

[42] Wu Lei, “The Oil Politics & Geopolitical Risks with China ‘Going out’ Strategy toward the Greater Middle East,” pp. 58- 61.

[43] Ron Bousso, “International Energy Agency to Offer China Room in Strategic Talks,” Reuters, April 4, 2013, http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/04/04/iea-china-idUKL2N0CR1IU20130404.

[44] Kabir Taneja, “India’s Importance in the Middle East,” War on the Rocks, April 22, 2014, http://warontherocks.com/2014/04/indias-growing-strategic-importance-to-the-middle-east-and-persian-gulf/.

[45] For example, China’s crude imports from Venezuela were more than doubled between 2009 and 2011. See, “As US Leaves, Oil-Hungry China Stuck in Middle East,” Wall Street Journal, June 27, 2012, http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2012/06/27/as-u-s-leaves-oil-hungry-china-stuck-in- middle-east/.

[46] International Energy Agency defines equity oil as the one “that [has been] obtained by control of rights to a given proportion of output from an oil concession in exchange for oil field exploration, development, or extraction services and investments, as opposed to trade or purchase-mediated access to oil.”

[47] International Energy Agency, “Country Analysis: China”.

[48] The CNOOC-Nexen deal was approved by the US government on February 12, 2013, overcoming the final hurdle. Previously, the deal also received approval from Canadian and British governments. Visit, Carolyn King, “Cnooc Purchase of Nexen Is Approved by U.S,” Wall Street Journal, February 12, 2013, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142412788732419620457829 986 2176958542.html.

[49] International Energy Agency, “Country Analysis: China”.

[50] Bhupendra Kumar Singh, “India’s Energy Security: Challenges and Opportunities,” Strategic Analysis, Vol. 34, No. 6, November 2010, pp. 802-803.

[51] Ibid., p. 803.

[52] See, Amy Myers Jaffe and Steven W. Lewis. “Beijing’s Oil Diplomacy,” Survival, Vol. 44, No. 1, Spring 2002, pp. 115–134; John Calabrese, “China and the Persian Gulf: Energy and Security,” The Middle East Journal, Vol. 52, No. 3, Summer 1998, pp. 351-366; John Lee, “China’s Geostrategic Search for Oil,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 35, No.3, 2012, pp. 75-92.

[53] Anthony Bubalo and Mark P. Thirlwell, “Energy Insecurity: China, India and Middle East Oil,” Issues Brief, Lowy Institute for International Policy, December 2004.

[54] Bernard D. Cole, “Chinese Naval Modernization and Energy Security,” paper prepared for the Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University 2006 Pacific Symposium Washington, D.C., June 20, 2006, p. 10.

[55] William Komiss and LaVar Huntzinger. “The Economic Implications of Disruptions to Maritime Oil Chokepoints,” CNA Analysis, 2011, pp. 12-13.

[56] The String of Pearls refers to a strategy to provide China with forward presence and military bases along the SLOCs from the South China Sea to the Persian Gulf in the Middle East. A pearl normally comes with facilities like airstrips and naval bases, logistics and intelligence. China currently has a number of pearls stretching from the Gulf of Hormuz to the Malacca Strait although not all of these pearls (bases) are fully militarized in the sense of US bases.

[57] For a detailed analysis, see, Serafettin Yilmaz (姚仕帆), “The Development of the Chinese Navy and Energy Security,” Global Review, Spring 2014, pp. 28-42.