- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- The Contexts of and Roads towards t...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- Three Features in China’s Diplomati...

- Middle Eastern countries see role f...

- China strives to become a construct...

- In Pole Position

- 'Afghan-led, Afghan-owned' is way f...

- Wooing Bangladesh to Quad against C...

- China's top internet regulator mull...

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- China’s Economic Initiatives in th...

- Perspective from China’s Internatio...

- Four Impacts from the China-Nordic ...

- Commentary on The U. S. Arctic Coun...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Identifying and Addressing Major Is...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Evolution of the Global Climate Gov...

- China’s Energy Security and Sino-US...

- China-U.S. Cyber-Nuclear C3 Stabil...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- Lies and Truth About Data Security—...

- Biden’s Korean Peninsula Policy: A ...

- Competition without Catastrophe : A...

- China's Global Strategy(2013-2023)

- Co-exploring and Co-evolving:Constr...

- 2013 Annual report

- The Future of U.S.-China Relations ...

- “The Middle East at the Strategic C...

I. State of the Art of China-Africa Peace and Security Cooperation

China always attaches great importance to China-Africa peace and security cooperation, referred by all and each FOCAC Ministerial Conferences. The 2006 China’s African Policy whitepaper lists the 4 dimensions of China-Africa peace and security cooperation, including military cooperation, conflict settlement and peacekeeping operations, judicial and police cooperation, and non-traditional security cooperation.[1] Then, in 2012 Chinese President Hu Jintao proposed the ICACPPS for upgrading this cooperation further. Currently, China-Africa peace and security cooperation is proceeding on the bilateral, regional and continental, and international levels simultaneously.

1.1 Bilaterally, China has close cooperation with African countries that have diplomatic relations with China. China always promotes high-level military exchanges between two sides and actively carries out military-related technological exchanges and cooperation. To strengthen bilateral peace and security cooperation, China and African countries jointly established relatively perfect institutions. 28 African countries have defense attachés in Beijing while 18 Chinese defense attaché offices in Africa plus 1 delegation of Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Chief Military Experts in Tanzania with more than 100 Chinese military officials there to help the country to build its military capacity. China now is training African military personnel mainly through receiving African military officials at Chinese National Defense University and sending military experts to African military universities or institutions. China now is assisting several African countries to build their National Defense University including Zimbabwe and Tanzania. China also has military technical and arms and ammunitions exchange with African countries for supporting defense and army building of African countries for their own security. Though in the absence of official data, some western observers claim that China shares some 15% of Sub-Saharan African arms market.[2] And some others claim that the proliferation of small arms and light weapons in Sub-Saharan Africa has significant contributions from China, especially the newly found weapons and ammunitions.[3]

Besides military cooperation and exchange, China has close cooperation with African countries bilaterally in the fields of judicial and law enforcement. The two parties learn from each other in legal system building and judicial reform so as to better prevent, investigate and crack down on crimes. Under the framework of FOCAC, there was a sub-forum named as “Forum on China-Africa Cooperation- Legal Forum” (FOCAC Legal Forum) that intends to build a dialogue mechanism for strengthening China-Africa legal exchanges and to promote the all-round development of China-Africa cooperation in various fields. The key issues related to peace and security topics covered by this sub-forum include experience sharing of legal system building and implementation, combating transnational organized crimes and corruption, cooperating on matters concerning judicial assistance, extradition and repatriation of criminal suspects, and fighting against illegal migration, improving exchange of immigration control information, etc.[4]

1.2 Continentally and regionally, China has cooperated with the African Union (AU), East Africa Community (EAC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Southern African Development Community (SADC), and so on. As mentioned by successive FOCAC ministerial conferences,

The two sides expressed their appreciation of the leading role of African countries and regional organizations in resolving regional issues, and reiterated support for their efforts in independently resolving regional conflicts and strengthening democracy and good governance and oppose the interference in Africa's internal affairs by external forces in pursuit of their own interests.[5]

China always tries hard to deepen cooperation with the AU and African countries in peace and security in Africa, to provide financial support for the AU peacekeeping missions in Africa and development of the African Standby Force, and to train more officials in peace and security affairs and peacekeepers for the AU. Meanwhile, China insists on the principle of African Solutions to African Problems (ASAP), respecting African ownership in terms of African peace and security affairs. In February 2013, when visiting China first time after her assumption of AU Commission Chairman, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma and Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi co-chaired the fifth strategic dialogue between China and AU, the first of which was held in 2008.Zuma thanked China for its enduring support for the peace and development in Africa, noting that Africa regards China as a trustworthy partner, and discussed with Yang Jiechi, then foreign minister how to deepen this partnership.[6]

China also plays a positive role in Africa’s continental and regional peace and security architecture building, including the AU’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the Africa Standby Force (ASF). Even though regional mechanisms for responding to conflict and insecurity have suffered from weak capacity, limited resources and in some cases an absence of political will, their role and influence are slowly growing. China is increasingly engaging with them and has provided modest amounts of financial support for peacekeeping operations and capability building efforts. For example, China has provided the AU with $1.8 million for its peacekeeping mission in Sudan and given smaller amounts of money to the AU mission in Somalia and West Africa’s sub-regional peace fund.

1.3 Multilaterally, China participates in various international efforts for improving African peace and security situations. China realizes the significance of increased exchanges and cooperation between the United Nations and the African Union in the field of African peace and security, and will continue to support the United Nations in playing a constructive role in helping resolve the conflicts in Africa, take an active part in the peace keeping missions of the United Nations in Africa and intensify communication and coordination with Africa in the UN Security Council. There are at least 3 examples that can prove China’s significant contributions in this regard.

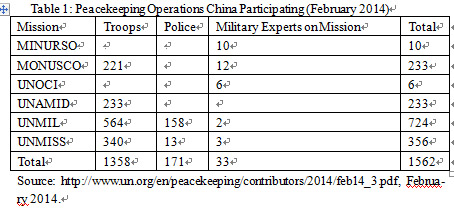

The first is China’s contributions to UN peacekeeping operations in Africa. Chinese peacekeeper sending began from the end of the 1980s when China sent its first election observers to Namibia in 1989. Since 2000, China has increased its troop contributions to UN peacekeeping missions by 20-fold.[7] The majority of these troops are deployed in Africa, where they contribute to efforts to help resolve some of the continent’s most persistent peace and security challenges. China has sent personnel to peacekeeping operations in Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Burundi, Sudan, Western Sahara, Ethiopia and Eritrea. Under the framework of the new type of strategic partnership between China and Africa, currently China participates into 6 peacekeeping operations in Africa with more than 1,500 peacekeepers and is the biggest peacekeeping troop contributor in the 5 permanent members of UN Security Council (table 1), shares about 3/4 of total Chinese peacekeepers worldwide.

The second case is China’s participation in the international anti-piracy efforts in Somalia coast. Since 2008, under the UN authorization, China joined the international fight against piracy for the first time. The goal is to protect the safety of Chinese ships and crews as well as ships carrying humanitarian relief materials for international organizations. As part of the international efforts to check piracy, a contingent from the Chinese navy, operating as an independent unit, has been offering escort and rescue missions along the Gulf of Aden. From 2008-2011, Chinese forces successfully conducted some 400 missions, escorting more than 4,300 vessels, and rescuing 55 ships in emergency, contributed a lot to the safety of the international waters.[8] It’s important to point out that China also tries to strengthen cooperation with other countries to help establish secure sea lanes off Somalia’s coast in the process.

And the third case is China’s mediation efforts in easing Sudan Darfur tension. China helped push forward the Sudanese government, the AU and the UN reaching consensus on the deployment of the hybrid force to Darfur in 2007. From mid-2006, the Chinese government began to persuade President Al Bashir to moderate his position. In their two meetings—at the first China-Africa Summit in November 2006 and Chinese President Hu Jintao’s Sudan visit in February 2007—President Hu talked to President Al Bashir about Chinese concerns with the Darfur crisis, and hoped Sudan government to accept the arrangement of a hybrid UN-AU forces.[9] Finally, the Sudanese government agreed to accept it in mid 2007, which did not come easily; and the international community has applauded China's efforts.

II. Main Characteristics of China-Africa Cooperation

At the bilateral, regional and continental, and global levels, China’s support for peace and security in Africa translates the country’s will to engage itself firmly, alongside the international community, in the maintenance of peace and security in Africa. This also demonstrates Beijing’s responsible attitude to world peace and stability and its support for the vision and purpose of the UN Charter. While deserved to be more publicized, China-Africa cooperation in the fields of peace and security is just at its very initial stage, with the following distinctive characteristics:

2.1 This cooperation is mainly focusing on traditional security issues. The 2006 China’s African Policy whitepaper addresses that,

In order to enhance the ability of both sides to address non-traditional security threats, it is necessary to increase intelligence exchange, explore more effective ways and means for closer cooperation in combating terrorism, small arms smuggling, drug trafficking, transnational economic crimes, etc.[10]

Even so, China-Africa cooperation is still traditional ones focused. For example, In Liberia, Chinese peacekeepers were active in supervising the implementation of the cease-fire agreement by the country’s various parties and ensured civilian protection, supported police reform and provided training to the local police. Chinese peacekeepers, through their engineering unit, also played a decisive role in the post-conflict reconstruction efforts of the country by helping local communities build and renovate some public facilities such as bridges, roads, and providing free medical treatments.[11] To be fair, China-Africa peace and security cooperation has omitted non-traditional security issues, such as terrorism, climate change, human security, drug trafficking, etc., to a large extent. The reasons lie in lacking of willingness, capability, experience, urgency, and so on. In one word, non-traditional security issues are not on the top of the policy priorities of both parties.

2.2 This cooperation is exclusively focusing on governmental level cooperation. Due to its sovereignty related nature, peace and security cooperation is of governmental business definitely. It’s important to say that there should have more room for non-state actors to participate in this cooperation. For example, there are a lot of state-owned companies having a role, not always positive one due to their poor corporation social responsibility performance, in shaping the China-Africa peace and security cooperation. However, both Chinese and African governments have not made efforts to include them into the China-Africa peace and security cooperation. Another example, while there are abundant intellectual resources in both China and Africa, including universities and think tanks, governments have not explored their full potential to contribute to peace and security cooperation.

2.3 Despite a lot of regional, continental and global level efforts, this cooperation remains a bilateral one. For example, there is a debate about the nature of FOCAC. For Chinese officials and scholars, FOCAC is a collective bilateral platform for designing China-Africa relations. Its negotiation process is between China and Africa as a whole, and then its implementation is decomposed between China and individual African countries. Thus, neither the negotiation process nor the implementation process is multilateral as the foreign scholars thought.[12] Thus, while FOCAC attaches importance to multilateral cooperation in terms of African peace and security, the bilateral one is the most important. And given the non-interventionist diplomacy, bilateral cooperation is more welcomed by both China and African countries.

III. Logics for ICACPPS

Why China proposed ICACPPS in 2012 rather than in 2006 or 2015? The answer lies in the development of China-Africa relationship itself. Entering into the 21st century, China-Africa has experienced a triple jump: in 2000, the two sides proposed to establish “a new long-term stable partnership of equality and mutual benefit”; in 2003, the two advocated “a new type of partnership featuring long-term stability, equality and mutual benefit and all-round cooperation”; and in 2006, the two were committed to “a new type of strategic partnership between China and Africa featuring political equality and mutual trust, mutually beneficial economic cooperation, and cultural exchanges”.[13] In other words, China’s engagement in Africa is approaching to a more and more comprehensive direction: from one-dimension relationship depends on emotional and/or ideological linkages through the 1950s to the early 1990s, to an all-round relationship relations with economic dimension added in since 1994-1995, then social and cultural exchanges since the early 21st century, and most recently the peace and security cooperation. In sum, it’s the transition of China-Africa relations that calls for greater engagement of China in African peace and security affairs.

There are significant and urgent calls for China’s Engagement. Since the end of the Cold War and especially after entering the 21st century, there are at least three main developments calling for China’s bigger role in African peace and security affairs, from international level, African continental level, and China-Africa bilateral relationship level.

3.1 On the international level, security and development, two traditionally separate policy areas, now are merging gradually. The end of the Cold War makes the world united into one by the increasing force of globalization and interdependence, which mixes the security issues with the development issues. During the Cold War, security and development were thoroughly institutionalized as separate “policy fields” with distinct objectives and means of intervention. Schematically, one may say that the Cold War effectuated a broad geographical ordering of security and development in which development concerned North-South relations, while security concerned East-West relations.[14]Following this geographical ordering of world politics was an institutionalization of two distinct fields of operations whose areas of concerns and modes of intervention diverged so as to create a conceptual and political division of labor, and a cognitive division of labor as “development studies”,[15]on the one hand, and “security studies”,[16]on the other hand, were linked up with and partly funded by the respective agencies in both policy fields.

This situation has been changing since the end of the Cold War. The prevalence and persistence of conflict in some of the world’s poorest areas have both frustrated development efforts and inspired a desire to understand and harmonize the objectives of security and development. Now, security and development concerns have been increasingly interlinked. Governments and international institutions have stated that they have become increasingly aware of the need to integrate security and development programs in policy interventions in post-conflict situations and in their relations to the growing category of failed and potentially ‘failing’ states. Two previously distinct policy areas are now increasingly overlapping in terms of the actors and agencies engaged and the policy prescriptions advocated. As former UN Secretary-General Kofi Anan says,

In the twenty-first century, all States and their collective institutions must advance the cause of larger freedom—by ensuring freedom from want, freedom from fear and freedom to live in dignity. In an increasingly interconnected world, progress in the areas of development, security and human rights must go hand in hand. There will be no development without security and no security without development. And both development and security also depend on respect for human rights and the rule of law.[17]

Thus, the framework of the “security - development nexus” has been hailed as a way of cohering national and international policy-making interventions in non-Western states, which has two significant policy implications, securitization of development policy, and developmentalization of security policy. Such a development asks for more consideration about the security environment, implications, and consequences of China’s engagement in Africa.

3.2 Entering into the 21st century, African security needs have changed significantly. Africa today is more peaceful than it was a decade ago. It should be recognized that progress has been made in overcoming the twin challenges of conflict and insecurity. While conflicts continue, African security challenges have shifted from wars and conflicts in the last decade of 20th century to post-conflict reconstructions entering into the 21st century. With the end of the Cold War, Africa, both governmental and non-governmental or rebellions forces, was freed from the influence of the bipolar system which made conflict as the main characteristics in much of Africa. As Christopher Clapham summarizes:

As the administrative reach of African states declined, with the shrinking of their revenue base and the spread of armed challenges to their power, so the number and size of such zones increased, … in the process creating a new international relations of statelessness.[18]

There were armed conflicts in sixteen of Africa's fifty-three countries in 1999; most of them defying the classical definition of war occurring between states. Since the early 1990s, Africa has suffered three particularly devastating clusters of interconnected wars centered around West Africa (Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Cote d’Ivoire), the Greater Horn (Chad, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan), and the Great Lakes (Rwanda, Burundi, Zaire/DRC, Uganda). Most casualties of these conflicts have been women and children, usually killed by the effects of diseases and malnutrition intensified by displacement.[19]

Entering into the 21st century, with the help of the international community, Africa has ended most of its wars and conflicts. Most of the former war-torn states now turn their eyes to re-building their countries, the effort called as post-conflict reconstruction. However, this task is full of obstacles. Armed conflict continues to affect several countries, including Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, and South Sudan, the most notable examples of embedded and cyclical conflicts with devastating humanitarian and economic costs. In other countries, environments of post-conflict fragility continue to cast shadows of insecurity while the unforeseen political transition in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya have cast northern Africa’s stability in a different light. In other regions still, localized and communal violence, low-level insurgencies and politically-related violence occur with alarming frequency.

3.3 The very nature of China-Africa relationship is changing as well. After half-century developments and under the shadow of international system transformation, China-Africa relationship now is facing at least three transitions: from ideological/emotional-based relationship to economic interest-based one, from economic interest promotion to economic interest protection, and from asymmetrical interdependence to symmetrical interdependence.

China-Africa relationship is transforming from a kind of relationship mainly based on emotional and/or ideological intimacy to one that based more on economic interest consideration, if not to say this process has finished. Looking back to China-Africa relationship during the period from the1950s to the early 1990s, emotional and/or ideological linkages, to a very great extent, supported this bilateral relationship and made it one of the closest relationships of China’s foreign exchanges. Meanwhile, because of geographical distance and weak economic conditions of both parties, the economic dimension of China-Africa relationship was quite weak. In 1950, bilateral trade volume was only 12.14 million dollars; in 1989, the figure was 1.17 billion dollars, with 9.7 times growth by 40 years. Since 1994-1995, China paid much more attention to Africa, with specific focus on economic relations. In 1996, bilateral trade volume increased to 4.03 billion dollars, nearly 4 times that of 1989.[20] Since then, the economic relation grows very fast with reaching 10 billion dollars in 2000, 100 billion in 2010, and nearly 200 billion in 2012. With economic linkages growing, bilateral trade frictions increase as well, which to some extent diminishes the emotional foundations of this bilateral relationship, along with the power shifting from the first generation leaders to the second generation across the whole African continent.[21]

The second transition China-Africa relations facing is the economic relationship now is shifting from promoting to protecting. Since the late 1990s, China initiated a “going global” policy for promoting Chinese interests, mainly economic interest, worldwide. The establishment of the FOCAC in 2000 strengthened this effort in Africa greatly.[22] Since then, we witnessed the fast growing presence of China’s economic interest all over the African continent. However, the security concerns of China’s presence in Africa are rising under the circumstance of global and African uncertainties, including mainly energy security, civilian protection, investment security, and others. In 2009 Africa’s oil exports to China represented 33% of China’s total oil imports, and 60% of total Sino-African trade.[23] As has been the case with oil companies from other countries operating in Africa, Chinese oil installations, and the Chinese citizens who work on them, have been targeted in numerous countries, including Nigeria, Ethiopia and Sudan. Since early 2011, the outbreak of the ‘Arab Spring’ highlighted the importance of protecting China’s overseas economic interests and national citizens. Based on the principle of “People First”, to protect overseas Chinese and economic interests is and will be one of the top priorities of China’s foreign policy in general and China’s Africa policy in particular.

While the above two transitions are already in the making, the third transition in Sino-African relations is a would-be one that will happen in the next few years or decade. I named this transition as from asymmetrical interdependence to symmetrical interdependence. As all know that the current Sino-African relationship is an asymmetrical interdependent one with China depends more on African natural resources and Africa depends more on opportunities along with China’s rise and Sino-African relations developments. However, there’re several developments that have potential for undermining the current interdependence between these two parties. The first is the slowing down of China’s economic growth that it is a natural development after 3 decades and more rapid growth with the signs have emerged early 2013, as the growth rates of the first quarter of 2013 was about 7.5%. While China is slowing down, Africa is rising, with 6 African countries on the list of 10 fastest growing in the first decade of the 21st century, and 7 African countries on the list of 10 fastest growing from 2011 to 2015. The third development that will change the interdependence between China and Africa is that Africa now is returning to the traditional powers’ strategic consideration and entering into that of the emerging powers, we have witnessed the recovery of EU-Africa Summit and Japan’s TICAD and the creation of India-Africa Summit, South Korea-Africa Summit, India-Africa Summit, and Turkey-Africa Summit.

Such three transitions ask for deep thoughts about the future of China-Africa relationship, especially how to maintain the current positive dynamics, and create new momentum. Among these measures, one full of promises is the peace and security affairs which Chinese is good at.

IV. Challenges for ICACPPS

More than one year has passed since the ICACPPS proposed, one finds more challenges for ICACPPS.

4.1 There is a huge expectation gap between the expectations of African, Chinese, and the rest of the world.

Due to its severe peace and security pressures, African does expect China to contribute a lot to African peace and stability. First of all, China is expected to provide more financial supports for African peace and security problem solving. With its remarkable records of economic growth since the 1980s, China now has to engage proactively with a changing global order. Increasingly, since the financial and economic crisis that erupted in America in 2008, China came under enormous pressure to redefine its role in and contribution to global problem-solving, with the African continent at the core. Meanwhile, African expects China can do a favor in every policy field, including for example, anti-terrorism, anti-piracy, peacekeeping, conflict resolution, crisis management, mediation, infrastructure building, post-conflict reconstruction, etc.

However, there are two opposite expectations regards to China’s role in African peace and security affair. The first one comes from Africans who are worried about losing ownership and controlling powers to China’s hand. For them, Africa has a long memory of being slaved by external powers, there is a potential of ‘second scramble for Africa’ in term of peace and security affair if Africa fully embraces China’s engagement. The second one comes from the former colonials and the world hegemony the United States. For these Western powers, China’s engagement means a zero-sum game that they will be replaced by China. While the West always calls for greater contributions from China to global public goods, the main content of what should China provide is not clear. According to my personal observation, there are only two kinds of public goods that the West welcomes. The first one is to share burden or more blatantly to pay more money, the second is a kind of damage controlling like in Sudan and Zimbabwe. However, these two kinds of public goods are negative ones from China’s perspective, because there is no any added-value in providing them. China can only contribute to preventing some bad things but not to promote some good things. If China wants to expand its provision of public goods from, for example, economic opportunities to security guarantee in the Asia-Pacific region, it will be encountered by the rebalancing efforts of other countries.[24]

Under these two opposite expectations, China-Africa peace and security cooperation will be very sensitive because every step will cause nerves, either of the pros or of the cons. Thus, it will be a serious task for both China and Africa to manage this expectation gap.

4.2 Parallel to the expectation gap, there is a capacity gap between the willingness and the available resources.

While China promised to strengthen peace and security cooperation with Africa, the capability deficit is a key challenge. Generally, the resources that China can assign to support Africa, including peace and security, are limited. China is still a developing state with uneven progress between different areas, as repeatedly highlighted in various official statements; consequently, a number of Chinese citizens question the rationale for providing international assistance citing that there are still huge urgent domestic needs. Taking medical team as example, in order to nurture a better international image, China continues with its tradition of sending medical teams with the best doctors, nurses, and technicians to Africa and other developing countries, which arguably increases the domestic healthcare needs and capability gap. This is a very tangible problem that Chinese citizens complain about.[25]

More specifically, China now has not well-prepared to provide significant support for Africa peace and security affairs. For example, China's peacekeeping contributions are appraised by the international community, while criticized not to contribute combating troops. Before May 2013, China only provided logistic supporting troops, such as medical teams, engineering companies. The reasons of no combat troops lies in, most importantly, lack of such a combat troop. Chinese peacekeeping training center has been established in 2009 and the first of its kind in the country; it is a joint project of the Ministry of National Defense and the UN.[26] To be fair, only 4 years after establishment, the center is at the very beginning stage of improving capability of Chinese peacekeepers, especially in terms of combating troops. Thus, while China is the biggest contributor of peacekeepers among the permanent members of the Security Council, its combat troops is still very small; and it's really a huge step for China to send its first combat troop to Africa when China declared to send its first security/police troop to UN peacekeeping operation in Mali May 2013.

4.3 There is still a policy gap because China and Africa hold different views on non-interference principle.

As is well known, China officially holds as a central premise of its foreign policy that governments should not interfere in the ‘internal affairs’ of other countries. This principle is welcomed by most African countries and people, while many western scholars and policymakers claim that China’s interpretation of non-interference and respect for sovereignty has affected, not always positively, modes of governance as well as ongoing conflicts. It is interesting to point out that in recent years, China has become somewhat more flexible in its interpretation of non-interference and has shown to be willing to take a more active diplomatic role in the resolution of internal conflicts. As already noted, Beijing eventually deployed significant diplomatic pressures on Khartoum to push the Sudanese government to accept the deployment of UN peacekeepers.

Contrary to China’s flexible adjustment, Africa has gradually moved from setting conditions for non-interference policy. The AU Charter declares that The Union shall function in accordance with:

(g) non-interference by any Member State in the internal affairs of another; Meanwhile

(h) the right of the Union to intervene in a Member State pursuant to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity;

In terms of policy, this means that African countries have agreed to pool their sovereignty to enable the AU to act as the ultimate guarantor and protector of the rights and well-being of African people. In effect, the AU has adopted a much more interventionist stance and has embraced a spirit of non-indifference towards war crimes and crimes against humanity in Africa.[27]

Interestingly, this policy gap between China and Africa as regards non-interference principle, once again magnifies the expectation gap and capability gap between China and Africa. Thus, to understand what role China will play in future African peace and security affairs, one has to keep an eye on the evolution of China’s non-interference principle.

V. Policy Prescriptions for ICAPPS

China-Africa peace and security cooperation has achieved significant progress in the past decades. To establish a new type of strategic partnership and build the ICAPPS, China and Africa should join hand together, while strengthening the traditional strong aspects of cooperation, attaching more importance to the following dimensions:

5.1 To broaden the scope of cooperation to cover most non-traditional security issues.

As mentioned above, current cooperation between China and Africa in peace and security is focusing on mostly traditional ones, including military exchange, military training, peacekeeping, anti-piracy, and so on. However, with the pacification of Africa conflict-torn countries and achievements of post-conflict reconstruction in transitional countries, looking to the mid-long term future, or for 20-30 years time frame, China’s support to African peace and security is possibly to be changed because of the fast changing environments. That is, while traditional security challenges are still there or will better up, the non-traditional security challenges will be highlighted in the near future. More and more security challenges will be linked with the development of African continent, including for example climate change, environmental degradation, human security, poverty reduction, unemployment or under-employment, etc.

Thus, there are two policy areas the China and Africa should pay more attention to, along with lasting emphasis on cooperation on traditional security. One is the peace and security cooperation under the post-2015 global development agenda. With the approaching end of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) set by the UN in 2000 by 2015, the discussion about post-MDG or post-2015 agenda now is growing. Taking a comprehensive approach of combining negative growth goals (MDGs) and positive growth goals (sustainable development goals (SDGs) initiated by the Rio 20 Summit in 2012), the post-2105 agenda has an ever-growing interest to integrate peace and security into it. Whatever the result will be, China and Africa should jointly address peace and security in the process of building the post-2015 agenda, and jointly develop capability of implementation after the launch of the post-2015 agenda.[28]

Another is the cooperation on governance experience exchange. As we all remember that in the late 1960s and 1970s, China faced rather serious security challenges than most African countries today. After adopting of the reform and opening up policy in 1979, China has experienced fast growing and lots of security challenges along with the fast growing that China has successfully addressed. Thus China now is only one or two steps ahead of Africa, and China’s experience of how to develop and how to solve security challenges arising in the process of developing will be of great relevance for Africa. This is the very reason why the Party School of the Central Committee, CPC held the conference on “China-Africa governance and development experience” on September 24, 2013.[29]

5.2 To motivate more non-state actors to contribute to building of ICAPPS.

China and African countries do prefer to governmental cooperation in terms of peace and security affairs. However, given the fact of increasing diversification of actors and interests involved in the China-Africa relations, central governmental focused approach needs to be supplemented by introducing all stakeholders into, including at least the following 3 elements.

First of all, there should be more rooms for provincial and local governments to play their roles in China-Africa peace and security cooperation. As Prof. Zheng Yongnian, a famous China expert in Singapore, pointed out rightly that China is a de-facto federalist state, with provincial and local governments have lots of bargaining chips with the central government. In the field of foreign economic cooperation, provincial and local governments have their own cost-benefits accounts, significantly different with the central governmental one.[30] This holds true as well in China-Africa relations. There are about 25 of 31provinces that have economic activities in Africa, 22 sending medical teams to Africa, and about 119 sister cities with Africa between 28 provinces and African countries.[31] The First Forum on China-Africa Local Government Cooperation, held in August 2012, argues for faster development of local governmental level engagement with Africa, with number of sister cities (provinces) reaching 220 in the next 5 years.[32]

Secondly, there is an urgent need for involving various companies, both state-owned and private ones, into the China-Africa peace and security cooperation. Considering the bad reputation of Chinese companies' corporation social responsibility (CSR) performance, how can China ensure, whilst doing business in Africa, that indeed its actions do not interfere with the aspiration of the populations for stability and development, by exacerbating already existing tension and does not increase inequalities in the country? In doing business in Africa, China may need to apply the “Do no harm” principle and principles of social corporate responsibility. Only by incorporating them, will the profit-seeking businessmen hold their responsibility.

Thirdly, China needs to develop its own private security companies to help promoting Africa peace and security. To have Chinese private security companies operating in Africa, will greatly help the China-Africa peace and security cooperation. On the one hand, Chinese private security companies will improve the CSR performance of Chinese companies in Africa due to common language, culture, practice, etc. On the other hand, the presence of Chinese private companies also will help China better communicate with local actors and better understand local security situation. However, due to the very slow domestic readjustment, most of Chinese private security companies have not been market-oriented reformed, and most of the reformed ones are very weak in terms of operating abroad.[33]

5.3 Finally, to rely more on multilateral cooperation platforms.

To promote peace and security cooperation, it's important to realize a balance between engagement and non-interference. However, as mentioned above, one of the main characteristics of China-Africa peace and security cooperation is bilateral, which risks greatly interfere into African domestic affair. Thus, a smart approach to address such a dilemma is to rely more on multilateral cooperation platforms.

First of all, the nature of African peace and security issues are multilateral in nature, to a very great extent. Because of the legacies of colonialism, African conflicts, both domestic ones and inter-state ones, involve regional powers because of either ethnic considerations or border disputes or resources competition or other reasons. Thus, to participate into one country’s post-conflict reconstruction, to some extent, influences the third parties, which calls for trilateral cooperation.

Secondly, as a result, peace and security cooperation in general asks for trilateral or multilateral cooperation and coordination. For example, peacekeeping or peace-building operations normally include at least three parties, the conflict-torn country, peacekeepers sending country/countries, and UN Peacekeeping Operation Department. Currently, except for sending peacekeepers, most of China’s participation in post-conflict reconstruction in Africa is bilateral.

And thirdly, thanks to the fast development of China-Africa relationship, many international actors call for trilateral cooperation with China in Africa, including the European Union, the United States, Japan, South Korea, and some other international organizations – both governmental and non-governmental. Meanwhile, these actors established their trilateral cooperation to pressure China to start trilateral cooperation with them.

It’s important to note that the key of such a trilateral and/or multilateral cooperation should be on African continental and regional organizations. As illustrated earlier, China has had close cooperation with African continental and regional organizations. This tradition will be kept as the ICAPPS mentioned as well. China should closely cooperate with African continental and regional organizations, especially in the fields of peacekeeping, peace and security financing, peacekeepers training, African Standby Force building, international arm control especially small arms and light weapons control, anti-terrorism, anti-piracy, transnational crimes, and so on. Promoting cooperation with African organizations will help China to overcome the dilemma between engagement and non-interference on the one hand, and to counterbalance the pressures of trilateral cooperation from EU, US, and other third parties significantly.

Source of documents:Global Review

more details:

[1] Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, China’s African Policy, 2006, Beijing.

[2] “Africa: China’s Growing Role in Africa - Implications for U.S. Policy,” AllAfrica, November 1, 2011, http://allafrica.com/stories/201111021230.html?viewall=1.

[3] Various presentations at the conferences of the Saferworld-supported Africa-China-EU Expert Working Group on Conventional Arms (EWG), July 2-3, 2013, Nairobi, Kenya, and November 13-14, 2013, Brussels, Belgium.

[4] ZhangWenxian and Gu Zhaomin, “China’s Law Diplomacy: Theory and Practice,” Global Review, Summer 2013, pp. 48-50.

[5] President Hu Jintao, “Open Up New Prospects for A New Type of China-Africa Strategic Partnership”.

[6] “China, AU pledge to Enhance Friendly Cooperation,” China Daily, February 16, 2013, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013-02/16/content_16225150.htm.

[7] Bates Gill & Chin-Hao Huang, “China’s Expanding Role in Peacebuilding: Prospects and Policy Implications,” SIPRI Policy Paper, No. 25, 2009.

[8] “China Conducts Anti-piracy Mission in Somalia,” CCTV English, February 23, 2012, http://english.cntv.cn/program/newshour/20120223/114644.shtml.

[9] Gareth Evans and Donald Steinberg, “China and Darfur: ‘Signs of Transition’,” Guardian Unlimited, June 11, 2007, http://www.crisisgroup.org/home/index.cfm?id=4891&l=1.

[10] Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, China's African Policy.

[11] Zhang Chun, “China’s Engagement in African Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Achievements and Future Developments,” in James Shikwati ed., China-Africa Partnership: The Quest for a Win-Win Relationship, Nairobi: IREN Kenya, 2013.

[12] Li Anshan, “Why the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation-Analyzing China’s Strategy in Africa,” Foreign Affairs Review (Chinese), Vol. 29, No. 3, 2012; Sven Grimm, “The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation – Its Political Role and Functioning,” CCS Policy Briefing, May 2012, Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch.

[13] President Hu Jintao, “Open Up New Prospects for A New Type of China-Africa Strategic Partnership”.

[14] See Geir Lundestad, East, West, North, South: Major Developments in International Politics since 1945, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

[15] Frederick Cooper and Randall Packard eds., International Development and the Social Sciences: Essays on the History and Politics of Knowledge, California: University of California Press, 1998.

[16] Pinar Bilgin and Adam. D. Morton, “Historicizing the Representations of ‘Failed States’: Beyond the Cold War Annexation of the Social Sciences?” Third World Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2002, pp. 55-80.

[17] In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All, Report of the Secretary-General, New York, N.Y., United States: United Nations, March 21, 2005, http://www.un.org/largerfreedom/contents.htm, accessed on June 20, 2005.

[18] Christopher Clapham, Africa and the International System: The Politics of State Survival, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 222.

[19] Paul D. Williams, “Africa’s Challenges, America’s Choice,” in Robert R. Tomes, Angela Sapp Mancini, James T. Kirkhope eds., Crossroads Africa: Perspectives on U.S.-China-Africa Security Affairs, Washington, D.C.: Council for Emerging National Security Affairs, 2009, p. 37.

[20] “Fifty Years of China-Africa Economic and Trade Relations,” Ministry of Commerce, July 16, 2002, http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/bg/200207/20020700032255.html; Li Yanchang, “The Present Situation and Prospects of the Sino-Africa Economy and Trade Relationship Development,” Journal of Shanxi Administration School and Shanxi Economic Management School, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2003, p. 45.

[21] Li Weijian et. al., “Towards a New Decade: A Study on the Sustainability of FOCAC,” West Asia and Africa, No. 209, September 2010, p. 8.

[22] Kerry Brown and Zhang Chun, “China in Africa –Preparing for the Next Forum for China Africa Cooperation,” Chatham House Briefing Note, June 2009, pp. 5-6.

[23] Such a dynamic is not unique to China. In 2008, oil accounted for 80% of all imports from Africa to the United States, the continent’s second largest trade partner after China. See Standard Bank, “China and the US in Africa: Measuring Washington’s Response to Beijing’s Commercial Advance,” Standard Bank Economic Strategy Paper, 2011; Standard Bank, “Oil Price to Remain at Two-and-a-half-year Peak,” Standard Bank Press Release, 21st February 2011.

[24] Zhang Chun, “Managing China-U.S. Power Transition in a Power Diffusion Era,” Conference Proceedings, The International Symposium on The Change of International System and China, September 27-28, 2013, Fudan University, Shanghai, pp. 176-177.

[25] Zhang Chun, “Projecting Soft Power through Medical Diplomacy: A Case Study of Chinese Medical Team to Africa,” Contemporary International Relations (Chinese), No. 3, 2010.

[26] “China’s Military Opens First Peacekeeping Training Center near Beijing,” People’s Daily, June 26, 2009, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90776/90785/ 6686691.html.

[27] Tim Murithi, “The African Union’s Transition from Non-Intervention to Non-Indifference: An Ad Hoc Approach to the Responsibility to Protect?” IPG, Vol. 1, 2009, pp. 94-95.

[28] As to the contents of peace and security in the proposed post-2015 development agenda, please see Thomas Wheeler, “Seven Ideas for Putting Peace at the Heart of Post-2015,” Saferworld, October 15, 2013, http://www.saferworld.org.uk/news-and-views/comment/111; and Thomas Wheeler, “A Reluctant Leader? China and Post-2015,” Saferworld, November 14, 2013, http://www.saferworld.org.uk/news-and-views/comment/117?utm_source=smartmail&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=China Post-2015 update November 2013.

[29] “Conference on ‘China-Africa Governance and Development Experience’ Held by CCPS,” FOCAC Website, October 9, 2013, http://www.focac.org/chn/xsjl/zflhyjjljh/t1086342.htm.

[30] Zheng Yongnian, De Facto Federalism in China: Reforms and Dynamics of Central-Local Relations, London: World Scientific, 2007; Zheng Yongnian , “De Facto Federalism and Dynamics of Central-Local Relations in China,” Discussion Paper, No. 8, China Policy Institute, Nottingham University, June 2006.

[31] China International Friendship Cities Association, November 20, 2013, http://www.cifca.org.cn.

[32] Beijing Declaration of the First Forum on China-Africa Local Government Cooperation, Beijing, 28 August 2012; “Li Keqiang Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the First China-Africa Local Government Forum,” Xinhua, August 27, 2012, http://www.newshome.us/news-2060728- Li-Keqiang-speech-at-the-opening-ceremony-of-the-first-China-Africa-Local-Government-Forum.html.

[33] Presentation by Mr. Xun Jinqing, CEO of the Shandong Huawei Security Group Co., Ltd, China, at the Conference “Managing Security and Risk in China-Africa Relations” on April 25-26, 2013, Center for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch University, South Africa.