- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- The Contexts of and Roads towards t...

- Three Features in China’s Diplomati...

- The Green Ladder & the Energy Leade...

- Building a more equitable, secure f...

- Lu Chuanying interviewed by SCMP on...

- If America exits the Paris Accord, ...

- Why China will drive global climate...

- How 1% Could Derail the Paris Clima...

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Evolution of the Global Climate Gov...

- Comparison and Analysis of CO2 Emis...

- China’s Energy Security and Sino-US...

- The Energy-Water-Food Nexus and I...

- Sino-Africa Relationship: Moving to...

- The Energy-Water-Food Nexus and Its...

- Arctic Shipping and China’s Shippin...

- China’s Role in the Transition to A...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- China's Global Strategy(2013-2023)

- Co-exploring and Co-evolving:Constr...

- 2013 Annual report

- The Future of U.S.-China Relations ...

- “The Middle East at the Strategic C...

- 2014 Annual report

- Rebalancing Global Economic Governa...

- Exploring Avenues for China-U.S. Co...

- A CIVIL PERSPECTIVE ON CHINA'S AID ...

Jan 01 0001

China’s Energy Security and Sino-US Relations

By

Energy is more than an ordinary commodity ─ it has always acquired political attributes. Access to energy resources is an important factor for the political and economic development of a country. It not only lays a solid material foundation for the economic development of a country, but also helps to increase its comprehensive national strength and enables the country to pursue an independent foreign policy and to have extensive influence in international politics. Global energy security is crucial to economic growth and people’s livelihood in all countries. Energy is also fundamental to the prosperity and security of nations. The advent of globalization, the growing gap between the rich and poor, and the need to fight global warming are all intertwined with energy concerns. There is a pressing need for strategic thinking about the energy security.

As the basis of fast-growing economic powerhouse, energy security is becoming an urgent priority for China’s economic and social development. China is the world’s second largest energy consumer, the uneven distribution of energy resources, the monopoly of energy resources and energy supply by developed countries and the complex geopolitical factors have landed China in an extremely severe situation in terms of obtaining energy from other countries. With the deepening of global economic integration, the influence of international energy geopolitics will grow increasingly. Thus, the whole world and China are currently facing the international energy geopolitics challenges in order to protect a reliable and affordable energy supply. It is no exaggeration to say that the success of dealing with the international energy geopolitics would determine the future prosperity of China’s economic and social sustainable development. As the two largest energy powerhouses in the World, U.S.-China cooperation in the energy security field is among the most noteworthy areas of bilateral cooperation, with some of the most notable successes.

I. Geopolitics and Energy Security

The energy geopolitical interactions focus on the following aspects: energy production, transportation and trade. For the developed countries, energy security is the availability and sustainability of sufficient supplies of oil and gas at affordable prices. Energy-exporting countries focus on maintaining the security and stability of demand for their exports. For the new developing powers (e.g. China and India), energy security now lies in their ability to rapidly adjust to their new dependence on global markets, which represents a major shift away from their former commitments to self-sufficiency.[①]

1.1 Imbalanced Supply and Demand

Geology and politics have created petrol-superpowers that nearly monopolize the world’s oil supply. Areas rich in oil resources are still at the center of geopolitical, political and military conflicts. Energy exporting nations use energy weapons to achieve their political and economic goals. Major energy suppliers—from Russia to Iran to Venezuela—have been increasingly able and willing to use their energy resources to pursue their strategic and political objectives.[②] It is also important to take a long-term perspective, deepen energy cooperation, increase energy efficiency, and facilitate the development and use of new energy resources. The energy production states control up to 77 percent of the world’s oil reserves through their national oil companies. These governments set prices through their investment and production decisions, and they have wide latitude to shut off the taps for political reasons.[③]

However, the oil production geography has changed overtime through 2004-2012 with the rise of the U.S. global oil supply and demand – Oil production capacity is spreading to some new actors. OPEC’s share in global oil production reduced from 58% in 2006 to 43% in 2012.[④] In 2004, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iraq and Iran were the four biggest giants in terms of proven oil reserves. The Middle East’s proven oil reserve was about 685.6 billion barrels and accounts for 65.35% of the world total, the Central-South America 96 billion barrels and 9.1%, the Africa 76.7 billion barrels and 7.3%, and the Former Soviet Union 65.4 billion barrels and 6.2%.[⑤] However, in 2011, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the US were the top three producers in the world. The Middle East’s proven oil reserve was about 807.7 million barrels and accounts for 78.4% of the world total, the Central-South America 328.4 million barrels and 19.7%, the Africa 130.3 million barrels and 7.8%, and the Former Soviet Union 126.0 million barrels and 7.5%.[⑥] During Obama’s first term of office, domestic crude oil production reached its peak in 14 years and the net import saw the nadir in 20 years. The U.S. has become the largest gas producer. The major oil producers and developed countries set prices through their investment and production decisions, and they have wide latitude to shut off the taps for political reasons.[⑦]

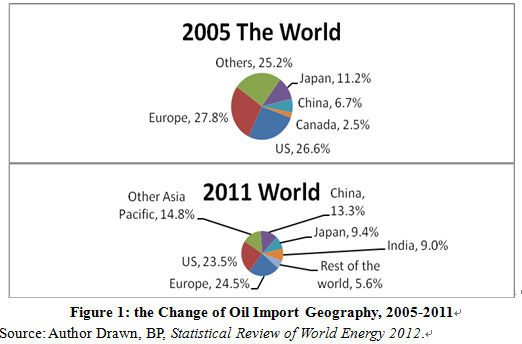

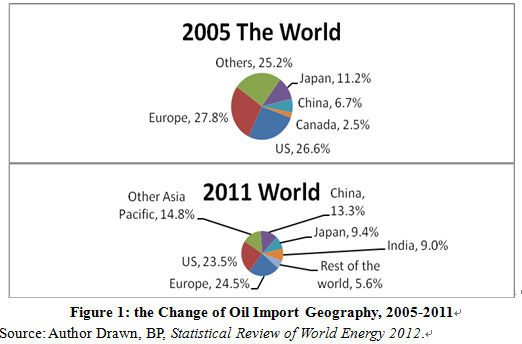

According to Figure 1 (the Change of Oil Import Geography), the global energy security landscape is evolving dramatically, with the demand centers shifting to newly emerging countries in Asia. “The rising influence of the developing world is disproportionate in energy markets: the non-OECD countries’ share of the growth in global energy consumption rose faster than their share of global economic growth over the same time period; it accelerated to more than 90 percent”.[⑧] Centre for global energy consumption turns to Asia and China has become the largest energy-consumption country. Demand driven by rapid rates of electrification in emerging Asia and the environmental profile of gas relative to coal and oil in American energy revolution drives the separation of global supply and demand. There is a pressing need for more strategic thinking about the international energy system.

However, we should not fail to see that supply and demand on the international energy market are balanced on the whole, and that there is no crisis on the supply side. At this point, the most critical thing is for all countries to work together for the stability of the world energy market, and to fuel the sustained growth of the world economy with sufficient, safe, economical and clean energy resources. On the other hand, it is also important to take a long-term perspective, deepen energy cooperation, increase energy efficiency, and facilitate the development and use of new energy resources. Energy cooperation and dialogues have been strengthened among and between OPEC countries, Russia, OECD countries, and newly-industrialized countries.

1.2 Change of Oil Geography after the Iraq War and US Shale Revolution

Since the second Iraq War in 2003, four dramatic changes happened in the international energy system: Firstly, the US took Iraq as an important oil diplomacy tool to stabilize the oil price and protect energy security because Iraq is still the world’s third largest proved oil-reserve country. Secondly, the Iraq war has weakened the proactive role of the OPEC in oil geopolitics.[⑨] Thirdly, Russia’s role as a major energy supplier is set to grow, and its oil diplomacy has changed the geopolitical picture of Europe and Asia. Fourthly, energy nationalism is surging in Latin America, particularly Venezuela.[⑩]

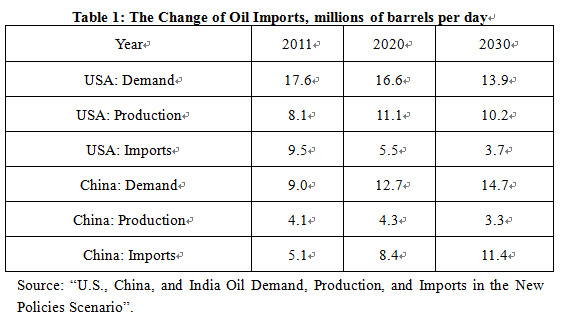

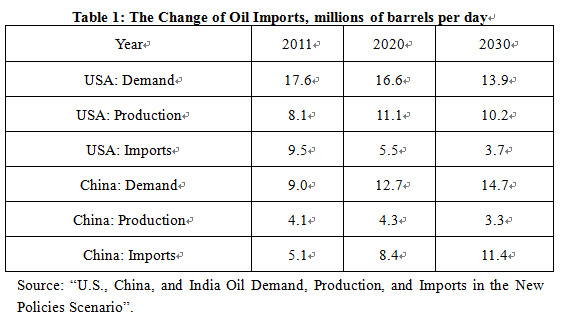

The U.S. energy independence enhanced the global energy security. The U.S. is currently undergoing an energy revolution, which will enable it to replace Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer within a decade and it will become a net exporter of natural gas by 2020.[11] According to the data of IEA, the U.S. oil production will reach 10 million barrels/day by 2015, and 11 million barrels/day by 2020, and the U.S. can finally meet its domestic energy needs by 2035.[12] Around 2030, the U.S. would only need to import about 3 million barrels of oil, much less than the 10 million barrels of China and 5 million of India. In addition, the U.S. will continue to reduce dependence on the oil from the Middle East, which has now dropped to about 14%.[13] The U.S. will continue to import from the Western Hemisphere, especially from Canada, which supplies 30% of America’s oil. By contrast, emerging oil-consuming countries like China and India are still mainly relying on the Middle East. Therefore, it is less likely for the U.S. and other main developing countries to be caught in a conflict.[14]

1.3 Power Struggle over Resources

Energy is fundamental to the prosperity and security of nations. The next-generation energy will determine not only the future of the international economic system but also the transition of power. As Daniel Yergin’s discussion of the “American oil hegemony”[15] and Paul Kennedy’s discussion about the “British coal hegemony”[16] indicate, the prerequisite condition of significant structural changes in the international system is an energy power revolution based on the emergence of next-generation energy-led countries. Many of the world’s major oil producing regions are also locations of geopolitical tension, and possibilities exist of unexpected supply disruptions. Instability in producing countries is the biggest challenge we face, and it adds a significant premium to world oil prices. Palestine, Iraq and Iran will push the geopolitical tension in the Middle East, the world’s largest oil producer. Darfur of Sudan, democratic transition in Congo and Zimbabwe, all of these pose potential dangers to African oil production. Because of such geographic imbalance, many actors are increasingly competing over the control of energy resources. In 1978, the major international oil companies dominated more than 70% of the production of oil and gas, but now it decreased to only 20%. Currently, the state-owned or state-controlled oil company control nearly 3/4 of the conventional proved oil and gas reserves of the world. This has fundamentally changed the relations between state-owned enterprises and private corporations, caused a lot of consequences. Meanwhile, it also provoked a battle over the Arctic, which remains the last unoccupied oil and gas territory of the world. The two energy crises in the 1970s have brought home to all countries the strategic importance of energy and the great impact of not having a stable supply of energy on the economy. With the end of the Cold War, the role of the military in national security has declined relatively, but the status of economic and energy security has steadily risen, instead of declining.[17]

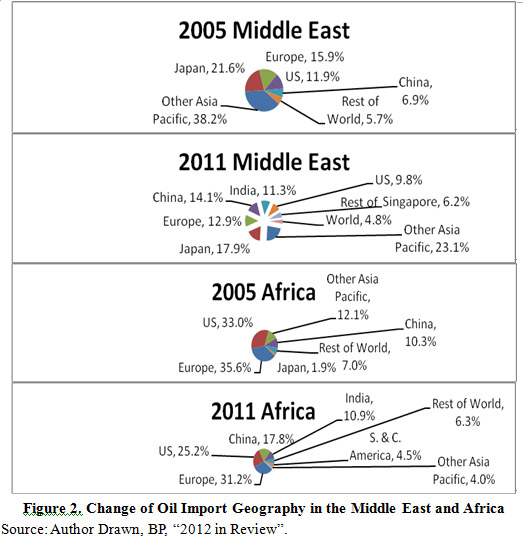

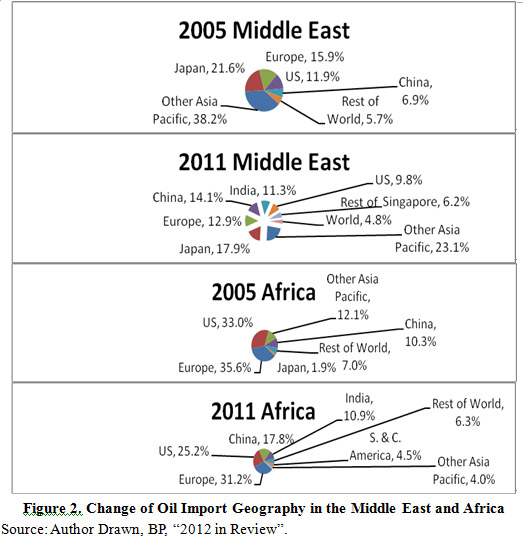

According to Figure 2 (the Change of Oil Import Geography in the Middle East and Africa), from a geo-strategic perspective, US worries about China’s rapidly increasing oil demands will certainly lead to the redrawing of the world’s oil political map in the coming decades. China is engaged in a search for oil that has it settle deals with Iran, Sudan, Burma, and other sources the US considers unsavory. China has already become the most important trading partner of the Gulf countries at present. In 2012, with an increase of 15.9% the bilateral trade volume between China and the Gulf Arab countries reached 155.03 billion dollars which accounted for almost 70% of the total trade between China and Arab countries.[18] Saudi Arabia is the largest trading partner of China in West Asia. In 2012, the bilateral trade volume reached 73.27 billion U.S. dollars with an increase of 13.9%.[19]

II. China’s Energy Security

The energy security problems China has to deal with are as follows. First of all, the oil consumption is heavily relying on import and it is reported that the degree of dependency has reach 58% in 2012. Secondly, the import of oil is excessively dependent on the Middle East. Thirdly, the import lanes of oil heavily focus on the Strait of Malacca. Fourth, China is compelled to pay extra costs for oil import because of the “Asia Premium”. For China’s external energy security, the Gulf region and energy transport are two issues to which should be attached the greatest importance. China is the newest player on the world energy market. Major Chinese oil companies started international operations in the 1990s and have made impressive progress. Peaceful energy development and international energy cooperation are the international dimensions of China’s energy policy. As a rising power on the peaceful development road, China’s energy strategy features mutual benefits and policy of building a harmonious world. China has taken an active part in energy cooperation with other countries on the basis of mutual benefit to ensure the stability of the regional and global energy markets. “The core of China’s energy strategy is to give a high priority to conservation, rely mainly on domestic supply, develop diverse energy resources, protect the environment, step up international cooperation of mutual benefit and ensure the stable supply of economical and clean energies.”[20] China also developed a new energy security concept that calls for mutually beneficial cooperation, diversified forms of development and common energy security through coordination.

2.1. China and the Gulf Region

As early as the 1970s, OPEC began to exert an extraordinary influence on the international energy system. From the international economics perspective, OPEC is an energy cartel created to control or monopoly the price and supply. OPEC can make the collective decision to limit or enlarge their oil production in order to monopoly the oil market and compete with non-OPEC oil producing states. In the long run, the influence of OPEC in international energy system is expected to rise. According to an IEA report, energy supply is increasingly dominated by a small number of major producers where oil resources are concentrated. OPEC’s share of global supply will grow to 48% by 2030 from 40% now and 42% in 2015.[21] In December 2006, OPEC’s Secretary-General announced that Sudan and Angola would become new members of OPEC which would significantly increase the world oil market share of OPEC. More than half of the crude oil imported by China is from the Middle East. In recent years, China has had fruitful cooperation with Gulf countries in energy and in other areas and has started the energy dialogue mechanism with them. Negotiations for a free trade agreement are underway. China has secured big energy projects in Saudi Arabia and Iran. There is a good prospect for energy cooperation between China and the Gulf region. Thanks to Saudi Arabia’s strong support, OPEC and China have entered into official exchange relations. The first China–OPEC Energy Roundtable was held in April 2006. Since the Iranian nuclear issue became a hotspot, China’s energy relations with Iran have become the target of criticism. Some scholars argue that China’s quest for energy might make China take sides with Iran, which might dilute the international efforts pressuring for Iran’s compliance. Such arguments are actually simplified judgments. China’s energy connections with Iran have been growing stronger in the last decade, but they are mostly embodied in the bilateral trade in the energy sector. Since China became a net importer of oil in the 1990s, its import from Iran stayed at the level of 10-15 percent of total imports. What should be especially mentioned is that beyond trade, China’s cooperation with Iran is modest. China signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Iran on energy cooperation in October 2004, which included the joint development of the Yadavaran oil field, which was thought to have a reserve of 17 billion barrels, and China’s import of gas from Iran.

2.2 China and Central Asia

Central Asian states, rich in oil and gas resources, are close neighbors of China. Their importance inworld energy politics is reflected not only in being the new sources of energy supply in the world, but also in their important role in the regional energy linkage. China has continued to strengthen energy cooperation within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). China and India, an SCO observer state, have gradually become the largest oil-consuming countries within the SCO, while Iran, Russia and Central Asian countries are the most important OPEC members. The 11 participating countries at the SCO conference should discuss how to improve the efficiency of cooperation and to put in place some kind of regional energy mechanism (or regional consultations and arrangements for consumption, production and transportation, etc.), which will have an important impact on the future international energy system. To enhance energy cooperation within the framework of the SCO is not only conducive to materializing China’s energy diversification strategy, it may also facilitate Sino–Russian energy cooperation. Once the Sino–Kazakh oil pipeline project is completed, Central Asian countries will increase their oil exports to China. Russia will also inject oil into this pipeline so as to make up for the inadequate rail capacity to ship its energy exports to China. Work is being done to extend this pipeline to Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries. The Sino–Kazakh oil pipeline will also be linked with the Russia-Iran oil pipelines. By then, there will be an oil shipping network conducive to multilateral energy cooperation within the framework of the SCO. In addition, the gas pipelines from Turkmenistan to China under the plan will run through Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which may make it easy to link with the natural gas pipelines between China and Central Asian countries and between China and Russia.

2.3 Transport-line and Energy Security

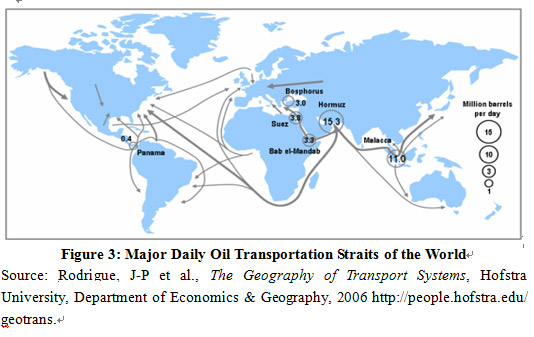

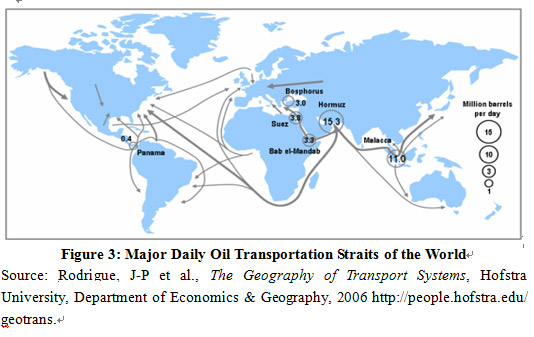

Energy is increasingly related to transport corridors. As the distribution of oil reserves does not correspond with that of oil consumption, most of the oil supply is transported through land or sea routes. Maritime oil tanker transport accounts for about 60% of the world oil shipments, while the rest 40% must be transported by the tubing or other land systems. The maritime oil transportation has a great effect upon the economic growth in Northeast and Southeast Asia. The Strait of Malacca is the second largest chokepoint in global oil transportation and trade shipments through this region accounts for about 30 percent of international trade. Yet this area has been plagued by piracy for a long time. After 9/11, in the face of a global anti-terrorism campaign, terrorists in Southeast Asia have moved their arena to the strategic sea lanes and chokepoints. Furthermore, the line between current terrorism and organized crime is getting dimmer, thus, it leaves a greater effect on the sea lanes security in the region of Malacca. The tankers shipping to Japan, China or the U.S. West Coast tankers must be made through the Straits of Malacca and Singapore Straits. About 2 million barrels of oil is transported to the East Asian countries through these two straits. And the tankers shipping to Europe and the U.S. East Coast are via the Suez Canal or the Cape of Good Hope.

There are mainly three imports of oil shipping lanes in China: (1) the Middle East routes, the Persian Gulf ─ the Strait of Hormuz Strait of Malacca ─ Taiwan Strait ─ China; (2) the African routes: North Africa ─ Mediterranean ─ Gibraltar strait ─ Cape Horn ─ the Strait of Malacca ─ Taiwan Strait ─ China; (3) Southeast Asia routes: the Strait of Malacca ─ the Taiwan Strait ─ China. That is to say, except the Pacific shipping lanes that China imports from South America countries such as Venezuela, China’s oil transportation from other directions must go through the Strait of Malacca. The Strait of Malacca as a shipping lane accounts for about 85% of China’s total oil imports, so the Strait of Malacca is the choke points of China’s oil imports. The actions that China actively built relationships with global oil producers to ensure its energy supply had caused the attention of the U.S. and Japan, increasing concerns about China’s proactive diplomacy and growing demand for energy could lead to conflict with America and Japan in the future.

III. China-US Energy Ties

At present, China’s dependency of coal import is 14.6%, and of oil import above 65.7%. As the two large consumers and importers in energy resources, China and the U.S. share common needs and foundation in energy, especially for oil and gas fields. Being the first two largest oil consuming countries, the U.S. and China should be entitled under the new energy concept toward energy issues to strengthen dialogue, communication and coordination, to build a constructive relationship full of healthy competition and strategic partnership. Former U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary Shriver pointed out that the growth of the U.S. and China’s oil demand may lead to two very different prospects: one may be a fierce competition for oil supply; the other is an increased mutual cooperation not only in oil but in all aspects. With occurrence of the U.S. shale gas revolution, the U.S.’s dependence on foreign energy is declining while the cooperation factors of the Sino-US energy relations are rising.

3.1 Position Change of China and the US in Energy Geography and Cooperation Foundation

Particularly, the oil demands and import continues to drop and the production is increasing in the U.S. while in China, the demands and import of oil has increased dramatically compared with the slight fall of production. Therefore, the energy relation between China and the U.S. has changed and the latter has increasingly become an important global producer which will lead to the reducing of competition between the two countries in the field of oil demands. The energy security problems China has to deal with are as follows. First of all, the oil consumption is heavily relying on import and it is reported that the degree of dependency has reach 58% in 2012. Secondly, the import of oil is excessively dependent on the Middle East. Thirdly, the import lanes of oil heavily focus on the Strait of Malacca. Fourth, China is compelled to pay extra costs for oil import because of the “Asia Premium”. By comparison, the degree of dependence of oil imports of the U.S. is increasing by years promoted by the shale gas revolution while its oil import from the Middle East is falling. The U.S companies try to expand oil exploration and controlling of non-OPEC countries especially for surrounding countries. The Middle East turns to actively develop energy relations with China influenced by the decrease of import from the U.S. As the largest trading partner of Saudi Arabia, China has surpassed the U.S.

People from the US government and academia choose to believe that the U.S. and China share common interests when facing challenges in the energy sector including free supply of oil as well as alleviation of environmental damages. Concretely speaking, there exists 3 opportunities for US-China cooperation. With regard to geopolitics of energy, both countries could jointly safeguard security and stability in the areas where oil is produced or transported; with respect to the orderly operation of international energy market, both countries could also join hands to arrange guidance to the oil price; energy technology promotion is the last but not the least field which both countries could establish partnership and collaborate to develop oil exploitation technologies, improve energy efficiency and solve the environmental problems caused by energy use. Economically, with rapid growth of China’s economy, the U.S. and China become more and more interdependent in economy as well as trade, which have made both countries enjoy great benefit. Since the US have become China’s second largest trade partner while China ranks third among US trade partners and also the fastest-growing export destination for US goods and services, at the same time, US is China’s top investor and vice versa, the US and China are closely bound up on international energy governance. Both countries could gain nothing if they collide for oil leading to the chaos of international energy system. China’s demand for energy stimulates economic growth in developing countries and impacts global oil market. For this reason, the U.S. and China should exert their influence on those oil-producing countries rather than compete with each other for oil.

The US and China share common interests in maintaining the stability of oil-producing countries. It is noteworthy that ensuring ample supply of oil on the global market has been put in one of several US energy policy priorities which could meet the needs of big oil consumers in the world. This provides spacious room for China-US cooperation on international energy policy and guaranteeing the steady supply of oil, which is the biggest converging point of their interests with respect to energy issues. The U.S. and China could make the global energy market function in a stable way by coordinating their energy policies within multilateral frameworks as well as taking concerted actions with other countries. The Middle Eastern countries are China’s most important energy suppliers. In view of US real dominance on the Middle East energy, China, when expanding its cooperation with oil-producing countries in that area, has to try to avoid conflicts with the US. Both the U.S. and China play vital roles in the energy transportation on the sea, hoping to build up safe and secure lanes for marine transport. Therefore, there are a lot of needs for both countries to launching initiatives on anti-terrorism or anti-piracy on the international sea lanes.

The positioning of the Sino-U.S. relationship on energy is emerging with positive changes. The US will be the biggest energy-producing country and China will be the biggest energy consumer in the future, as the global energy production center shifts to the US. By 2020, the Sino-US energy relationship will change gradually with the falling demand and increasing production and export of US energy and the increasing demand and import and the falling production on the side of China. The USA and China will be mutual partners but not competitors on energy. Second, it is in the US interest to maintain the global energy market. The Obama administration and his predecessors have different energy policies to China. Obama welcomed China to invest in North America. From 2011, China’s energy investment in North America has been increasing greatly. Especially the Foreign Investment Review Board of the US approved the China National Offshore Oil Corporation buying Nixon of Canada for 12 billion, which indicated that US wariness of investment from China is decreasing. The US has technology advantage in natural gas, nuclear power, coal and renewable energy, which means that China is interdependent with the US.[22]

Thus, the energy relation between China and the U.S. needs to be repositioned. With the global energy production axis shifting to the North America, the U.S. will become the largest energy production country in the future while China will be the largest consumer. Under this circumstance, Sino-US cooperation in the energy field has been changed from competitors to mutual benefit partners. As recently, the acquisition of Nixon Company of Canada by the China National Off shore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) won the approval of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., which means the U.S. has reduced wariness of China’s energy investment and the Sino-US energy relation is pushed forward in a benign and complementary direction. The driving force of the energy strategy of the U.S. is technological innovation. The transition from a country comparatively lack of gas and oil to a large energy export country in the future is closely related to its innovation in energy technology. China may improve technology and enhance capacity of overseas development by cooperating with the U.S.

3.2 Gulf Region

In the Middle East, China and the United State share common interests which include maintaining security and stability of oil production and transportation in geopolitics, guiding oil price by cooperation in orderly operation of international energy market and also for energy technology, both China and the U.S. may conduct cooperation in oil exploration, energy conservation and efficiency as well as energy related environmental protection. The Middle East is a crucial source of oil import for China and since the politics and economy of this area is under the actual control of the U.S., China must handle relations with the U.S. properly in order to expand cooperation with Middle Eastern oil-producing countries. Particularly, the trilateral relations of China, the Middle East and the US are the key elements measuring the Sino-US energy relationship. The major consuming countries and importing countries in the energy sector can find their common interest, especially to oil of energy sector in the Asia-Pacific. China and the U.S. can avoid deteriorating their political relationship but cooperate in the energy and trade sectors to promote the stability and development on the global energy market. The U.S. has advantage in natural gas, nuclear energy, coal and renewable energy, and China’s reliance on the U.S. for energy is growing, so it is important for China to cooperate with the U.S. but not conflict with it. The Middle East has actively developed the energy relationship with China. Now China is the most important trade partner to Gulf countries. On the one hand, China and the US have common interests in maintaining the security of Middle East from the perspective of energy geopolitics. On the other hand, it is China’s chief strategic direction to ensure the ample supply from the Middle East. China has to rely on sea power to maintain the security of increasing oil and gas import, and also increase investment in gas and oil in the world, as the US army has controlled the import value of China’s oil and gas. But all this will raise US concerns about the cooperation between China and the Middle East as the challenge to US sea power. Specifically, when the US does not need to import from the Middle East and is energy independent as a result of the “Energy Revolution”, it will be able to “change” the Middle East. And this will threat China’s energy security.

3.3 Energy Transport

Generally, the global system of energy transport governance is dominated by the US. US-led Western nations formulated a series of governance mechanisms and rules of navigation and transport. On the whole, the current system of energy governance favors global energy security; however, the geopolitics master Mahan thought that the key to dominate the world lies in the ability to compete for energy.[23] The dominance over the oil transportation is the power foundation for sea powers like the U.S. and the United Kingdom to have ruled the international system for a long period of time. The competition between sea powers (the U.S. and the United Kingdom) and continental powers for energy has determined the rise and fall of hegemony in the last 400 years. Without doubt, the Asia-Pacific region will be the strategic priority of Obama’s second-term. The influence of China and the U.S. and the allocation of resources will be the focus as the Asia-Pacific becomes the center of power struggles and competitive interests. Many scholars believe that China will be considered as a disincentive by the U.S. It seems that the Chinese oil-transit channels were seen as the starting point of US Asia-Pacific strategy. Most of the oil imports are across the Indian Ocean routes (the gulf across the Suez Canal- Chinese ports), where the sea islands of China also plays a key role. Over 85% of the oil imports of China, Japan and South Korea pass through the routes. Now some sea islands and reefs of China are occupied by the neighboring countries, and behind them is the U.S. intending to dominate the Indian Ocean routes to contain China. Tom Donilon argued, “the promise of offshore energy resources is contributing to tensions in the South and East China Seas that will test East Asia’s political and security architecture. While the U.S. has no territorial claims there, and does not take a position on the claims of others, the U.S. firmly opposes coercion or the use of force to advance territorial claims. We have consistently made clear our position that only peaceful, collaborative and diplomatic efforts, consistent with international law, can bring about lasting solutions that will serve the interests of all claimants and all countries in this vital region.”[24] As more than 85% of the petroleum imported to China is shipped through the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea route, it is most vulnerable and could easily be blocked and controlled.

Most of the oil trade in the world is transported by sea. To ensure safety and freedom of sea navigation, particularly security and safety along the key international waterways, China has conducted cooperation with various countries in countering maritime terrorism and sea piracy. But the energy exploration and production center is shifting to North America. The U.S. will be the biggest energy producer, and China will be the biggest energy consumer. It is obvious that China and the U.S. are complementary in the energy sector. One of the topics for the presidential debates between Obama and Romney has been energy. Obama emphasized that the U.S. was becoming resource power and adjusting its energy strategy. The U.S. crude oil production has reached the highest level in 14 years but the net imports volumes are the lowest in 20 years. The U.S. has already been the largest natural gas producer. The Asia-Pacific region has been the top priority for China energy imports. For example, China’s reliance on coal imports has been 14.6%. Most of the imports are from the Asia-Pacific region, 6.4 million tons from Indonesia, followed by 3.2 million tons from Australia, 2.2 million tons from Vietnam, 2 million tons from Mongolia and 1 million tons each from North Korea and Russia. China’s nickel ore imports from both Indonesia and Philippines are over 2 million tons, which is crucial to the electricity sector. Ensuring access to adequate, reliable, affordable and clean energy is a key challenge facing the countries of the Asia-Pacific region, and indeed the whole world. For the Asia-Pacific, energy security is a key issue because there are large energy users without sufficient domestic reserves and large energy producers with surplus capacity in this region. It is also an issue that has taken on added importance because the success of Asia-Pacific economies and the rapid development of large parts of the region have brought future energy needs into economic and political focus.

3.4 Bottom-up Cooperation

China should pay attention to avoiding governmental action and mainly rely on non-governmental organizations and companies to serve China’s interests through cooperation with its US counterparts. There are three kinds of investment for Chinese oil companies’ “go out strategy”: first is wholly-owned or sole investment, second is joint venture participation, and the last is non-equity arrangement. For the wholly-owned or sole investment, China’s NOCs will hold 100% share though buying undeveloped oil & gas fields or the shares of oil companies with reserves. However, the host government will worry about the direct control of reserves by foreign NOCs and there impose strict supervisions. Thus, the wholly-owned or sole investment is not the best choice for China’s NOCs when the resource nationalism is rising everywhere (e.g., the case of CNOOC purchase Unocal). Joint venture participation includes two types: Share—cooperation with host national oil companies and cooperation with international oil companies (IOCs). From the four NOC forums in Saudi Arabia, we can see that the host government welcomes the share cooperation with China’s NOCs. China’s NOCs are searching outside their home countries for equity oil and gas and are forming joint ventures and alliances with IOCs. NOCs need IOC technology and oil-field management expertise and are inviting IOCs to serve as contractors for field development--a role formerly filled by service companies. Joint venture participation will reduce the economic, political and social costs and risks for China’s NOCs’ “go-out strategy”, and should be put highest priorities. Thirdly, the non-equity arrangement includes a lot complex contracts: concession, production sharing, oil field service, rent resource, and technology aid. Depending on NGOs and corporations to achieve the energy interests in the world’s chief energy production areas. Energy issues are naturally beyond national borders. As political entities, nation states cannot fully participate in the whole process of cooperative development of energy including negotiation, contract signing, exploiting and settlement of dispute. The cooperative development of energy needs participation by governments, companies, investor, etc. The main carrier of China’s interests in the Middle East lies between nation states and investors and also between implementers of host countries and investors. Moreover, energy cooperation involves research and development, information and human bridge, science and technology cooperation. Because the U.S. carries long term wariness of the rise of China and as the “tap” of global oil, the Gulf area is the fulcrum of international geopolitics and also the core of sea power hegemony of the U.S., more governmental acts will attract more wariness.

IV. The Potential Conflicts in China-US Energy Ties

China’s ever-growing oil demand necessarily means more fierce competition with the US for world oil resources. There are possibilities that energy topics may be used as pretexts for intensifying China-US competition, misjudgment and interest damage to each other instead of important part of constructive cooperation.

4.1. Geopolitical Issues

From geopolitical side, the energy geo-strategy of the U.S. focuses on Russia-US energy cooperation, and leading the process of oil and gas exploitation in Africa and the Caspian Sea, which could weaken the power of OPEC. By Launching the War in Iraq, US have established new geopolitics of oil. Governments of the U.S. and China as well as oil companies from both countries have contests in many countries such as Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Nigeria, the Republic of Cameroon, and the Republic of Chad.

First of all, nations around the world are striving for the abundant oil resources in the Gulf area. After the Iraq War, the U.S. has basically controlled the oil in Middle East and its strategic output channels. However, China’s oil import accounts for more than half of its total from the Middle East, and it mainly transports by loan tankers through long-distances by sea. Meanwhile, it goes through the offshore oil transportation chokepoints controlled by the U.S. (such as the Suez Canal, Mandela, the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Malacca strait, etc.), once the China-U.S. relations get deteriorated, the U.S. is likely to use its oil hegemony system to block the oil to China. In extreme cases, China may not get the Middle East oil at all. It will not only have great impact and threats on the concept of peaceful development of China’s oil security as well as its international energy cooperation, it may also seriously affect Sino-U.S. relations. China is gaining a cooperation momentum with Gulf countries and has successfully won bid for key energy projects in Saudi Arabia and Iran, which has upset the U.S. and other Western countries. In this background, China’s further cooperation with Gulf countries might be disturbed by the U.S. Quite a few of American scholars tend to see Middle Eastern countries maintaining oil sovereignty and the regional contradictory factors as the main factor of oil instability. They also accused the lagging economic system of the Middle East countries not being able to produce oil market price formation and decision mechanism. As a matter of fact, the escalation of the war against terrorism had deepened the contradiction between the U.S. and the Islamic world, which painted the oil market in the Middle East and even in the rest of the world with strong political overtones.[25]

Secondly, the adjacent Central Asian countries with abound oil and gas resources have ascended as China’s leading energy suppliers. Central Asia, as a new source of global energy and regional energy hub, has earns its position in international energy politics. With regard to this, the U.S. takes every effort to intervene in the oil and gas projects initiated by China and Kazakhstan or Turkmenistan as shareholders, in order to cut off China’s oil and gas supplies from Central Asia. The key to the geopolitics of oil-gas in the Caspian lies in the fierce competition over determining the main oil and gas pipelines among the U.S., Russia and Iran.[26] Due to the special geography, history, religion and ethnic relations in the Middle East and central Asia, the three confrontational countries over the energy and geopolitical competition in the Caspian will inevitably affect the stability of the oil supply security in the Middle East. Except for the direct oil interests, the strategic objectives of America’s geopolitical expansion into Central Asia also includes the following three aspects: supporting the Central Asian countries gradually getting rid of Russia’s sphere of influence and excluding them from Russia’s economic and political integration; controlling the oil pipelines and promoting NATO’s eastward expansion, squeezing Russia’s strategic space toward south and west; and continuing to suppress Iran to achieve the dominant place over the central Asia and the gulf. China and Kazakhstan ensure the China-Kazakhstan oil pipeline project completed and put into production on schedule, provides China with a relatively safe onshore oil channel. America is not willing to let it go, the U.S. had not only promoted building the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceylon oil pipeline that leading westward to shunt the Caspian and central Asia, but also strengthened the infiltration of Central Asia in the name of counter-terrorism.

Thirdly, The US is competing with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the BRICS countries for energy. Either SCO or BRICS are attempting to organize certain system of energy consumption, production, and transportation, making consultations and arrangements in these sectors. The U.S. could undermine China’s efforts of engaging more with core oil exporting countries than peripheral ones. Senator Lisa Murkowski from Alaska warns that “China has stepped into our backyards grabbing energy and raw materials”. “Chinese companies are enthusiastic about making profits without scruple in the countries disgusted by the West, which breaks geopolitical balance and also alienates the existing equilibrium relationship between oil-producing countries and the world’s leading oil companies.”[27] From China’s energy corridor and diversification of energy import side, in the first place, China-US competition for oil and other natural resources will cause negative effects on bilateral relations. Countries like Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia, Nigeria and Sudan who are eager to deepen ties on oil trading with China are disgusting in the eyes of the US and other western countries.

Fourthly, Africa is also becoming an increasingly important source of energy for China. More than half of Sudan’s oil production has been exported to China. China had participated in Africa’s oil and gas processing and transporting, holding a 40% stake in Sudan’s largest oil companies. As regard to China’s cooperation with Sudan, the U.S. criticized China for supplying weapons to Sudan, neglecting the region’s human rights, rule of law as well as other possible problems that might do harm to other countries, which went against America’s interests. Besides, Chinese oil companies in Africa had increased the opportunities for the economic development of the petroleum exporting countries in Africa, helped to push the international community to take responsibility to help Africa to deal with the challenges.

4.2. China’s NOC’s Behaviors

China had launched a diplomatic offensive to ensure its energy security, making America increasingly anxious and dissatisfied by cooperating with countries hostile to the U.S. The U.S. frequently accuses China of buying overseas energy in recent years: “China was determined to lock the limited remaining oil of the world,” “China had further aggravated the burden of the international oil supply, causing a rise of the oil price”.[28] The U.S. believes that China aims to get the oil by ignoring the issues such as human rights protection, nuclear non-proliferation and improving the level of governance. China pointed out that under the circumstance that the resources of the reliable countries had been occupied, domestic enterprises can only walk into the high risky countries. The U.S. intention of hedging China is self-evident. As regard to the global energy market, the U.S. wants to have a fair competition environment. China fears that it will make itself at a disadvantage by competing with unequal competitors with the same rules.

In conclusion, energy is fundamental to the prosperity and security of nations. The global energy system is open, which lies in the interdependence among production states, consumption states and transit states. For China and the U.S., the common challenge is to recognize the reality of their interdependence and to reach an understanding so as to build a sustainable energy security framework. The U.S. and China share common interests in maintaining the stability of oil-producing countries. It is noteworthy that ensuring ample supply of oil on the global market has been put in one of several U.S. energy policy priorities which could meet the needs of big oil consumers in the world. This provides spacious room for China-U.S. cooperation on international energy policy and guaranteeing the steady supply of oil, which is the biggest converging point of their interests with respect to energy issues. The U.S. and China could make the global energy market function in a stable way by coordinating their energy policies within multilateral frameworks as well as taking combined actions with other countries. Middle Eastern countries are China’s most important energy suppliers. In view of U.S. real dominance on the Middle East energy, China, when expanding its cooperation with oil-producing countries in that area, has to try to avoid conflicts with the U.S. Both the U.S. and China play vital roles in the energy transportation on the sea, hoping to build up safe and secure lanes for marine transport. Therefore, there are a lot of needs for both countries to launch initiatives on anti-terrorism or anti-piracy on the international sea lanes. China and the U.S. can avoid deteriorating their political relationship but cooperate in the energy and trade sectors and to promote the stability and development in the global energy market.

Looking into the future, China and the U.S. should avoid the possibility that the competition between the two countries turns into an adversarial relationship. In addition, they may cooperate in energy, economics and trade to promote the stability of market regulation and mature development of global energy. The U.S. gains international technology and resource dominance in gas, nuclear energy, coal and renewable energy while China’s interdependency with the U.S. in these fields is increasing. China can choose to play a constructive role in a U.S.-dominated system of energy governance when the energy relations between the U.S. and China tend to be mutually dependant. The two should avoid strategic distrust that come with power and economic ties transformation and China should guard against the U.S. becoming an interfering factor in China’s overseas energy supply. With their special status and roles, to protect the access and price to energy resources is the important task for both countries. Consequently, it is not only for China and the U.S. but also for other countries to cooperate in the energy sector. As Daniel Yergin said, “it is advisable and urgent to engage China in the global trade and investment system instead of making China like a peddler to bargain with every country, which is helpful to China and the other countries in the energy security system”.[29]

As the basis of fast-growing economic powerhouse, energy security is becoming an urgent priority for China’s economic and social development. China is the world’s second largest energy consumer, the uneven distribution of energy resources, the monopoly of energy resources and energy supply by developed countries and the complex geopolitical factors have landed China in an extremely severe situation in terms of obtaining energy from other countries. With the deepening of global economic integration, the influence of international energy geopolitics will grow increasingly. Thus, the whole world and China are currently facing the international energy geopolitics challenges in order to protect a reliable and affordable energy supply. It is no exaggeration to say that the success of dealing with the international energy geopolitics would determine the future prosperity of China’s economic and social sustainable development. As the two largest energy powerhouses in the World, U.S.-China cooperation in the energy security field is among the most noteworthy areas of bilateral cooperation, with some of the most notable successes.

I. Geopolitics and Energy Security

The energy geopolitical interactions focus on the following aspects: energy production, transportation and trade. For the developed countries, energy security is the availability and sustainability of sufficient supplies of oil and gas at affordable prices. Energy-exporting countries focus on maintaining the security and stability of demand for their exports. For the new developing powers (e.g. China and India), energy security now lies in their ability to rapidly adjust to their new dependence on global markets, which represents a major shift away from their former commitments to self-sufficiency.[①]

1.1 Imbalanced Supply and Demand

Geology and politics have created petrol-superpowers that nearly monopolize the world’s oil supply. Areas rich in oil resources are still at the center of geopolitical, political and military conflicts. Energy exporting nations use energy weapons to achieve their political and economic goals. Major energy suppliers—from Russia to Iran to Venezuela—have been increasingly able and willing to use their energy resources to pursue their strategic and political objectives.[②] It is also important to take a long-term perspective, deepen energy cooperation, increase energy efficiency, and facilitate the development and use of new energy resources. The energy production states control up to 77 percent of the world’s oil reserves through their national oil companies. These governments set prices through their investment and production decisions, and they have wide latitude to shut off the taps for political reasons.[③]

However, the oil production geography has changed overtime through 2004-2012 with the rise of the U.S. global oil supply and demand – Oil production capacity is spreading to some new actors. OPEC’s share in global oil production reduced from 58% in 2006 to 43% in 2012.[④] In 2004, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iraq and Iran were the four biggest giants in terms of proven oil reserves. The Middle East’s proven oil reserve was about 685.6 billion barrels and accounts for 65.35% of the world total, the Central-South America 96 billion barrels and 9.1%, the Africa 76.7 billion barrels and 7.3%, and the Former Soviet Union 65.4 billion barrels and 6.2%.[⑤] However, in 2011, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the US were the top three producers in the world. The Middle East’s proven oil reserve was about 807.7 million barrels and accounts for 78.4% of the world total, the Central-South America 328.4 million barrels and 19.7%, the Africa 130.3 million barrels and 7.8%, and the Former Soviet Union 126.0 million barrels and 7.5%.[⑥] During Obama’s first term of office, domestic crude oil production reached its peak in 14 years and the net import saw the nadir in 20 years. The U.S. has become the largest gas producer. The major oil producers and developed countries set prices through their investment and production decisions, and they have wide latitude to shut off the taps for political reasons.[⑦]

According to Figure 1 (the Change of Oil Import Geography), the global energy security landscape is evolving dramatically, with the demand centers shifting to newly emerging countries in Asia. “The rising influence of the developing world is disproportionate in energy markets: the non-OECD countries’ share of the growth in global energy consumption rose faster than their share of global economic growth over the same time period; it accelerated to more than 90 percent”.[⑧] Centre for global energy consumption turns to Asia and China has become the largest energy-consumption country. Demand driven by rapid rates of electrification in emerging Asia and the environmental profile of gas relative to coal and oil in American energy revolution drives the separation of global supply and demand. There is a pressing need for more strategic thinking about the international energy system.

However, we should not fail to see that supply and demand on the international energy market are balanced on the whole, and that there is no crisis on the supply side. At this point, the most critical thing is for all countries to work together for the stability of the world energy market, and to fuel the sustained growth of the world economy with sufficient, safe, economical and clean energy resources. On the other hand, it is also important to take a long-term perspective, deepen energy cooperation, increase energy efficiency, and facilitate the development and use of new energy resources. Energy cooperation and dialogues have been strengthened among and between OPEC countries, Russia, OECD countries, and newly-industrialized countries.

1.2 Change of Oil Geography after the Iraq War and US Shale Revolution

Since the second Iraq War in 2003, four dramatic changes happened in the international energy system: Firstly, the US took Iraq as an important oil diplomacy tool to stabilize the oil price and protect energy security because Iraq is still the world’s third largest proved oil-reserve country. Secondly, the Iraq war has weakened the proactive role of the OPEC in oil geopolitics.[⑨] Thirdly, Russia’s role as a major energy supplier is set to grow, and its oil diplomacy has changed the geopolitical picture of Europe and Asia. Fourthly, energy nationalism is surging in Latin America, particularly Venezuela.[⑩]

The U.S. energy independence enhanced the global energy security. The U.S. is currently undergoing an energy revolution, which will enable it to replace Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer within a decade and it will become a net exporter of natural gas by 2020.[11] According to the data of IEA, the U.S. oil production will reach 10 million barrels/day by 2015, and 11 million barrels/day by 2020, and the U.S. can finally meet its domestic energy needs by 2035.[12] Around 2030, the U.S. would only need to import about 3 million barrels of oil, much less than the 10 million barrels of China and 5 million of India. In addition, the U.S. will continue to reduce dependence on the oil from the Middle East, which has now dropped to about 14%.[13] The U.S. will continue to import from the Western Hemisphere, especially from Canada, which supplies 30% of America’s oil. By contrast, emerging oil-consuming countries like China and India are still mainly relying on the Middle East. Therefore, it is less likely for the U.S. and other main developing countries to be caught in a conflict.[14]

1.3 Power Struggle over Resources

Energy is fundamental to the prosperity and security of nations. The next-generation energy will determine not only the future of the international economic system but also the transition of power. As Daniel Yergin’s discussion of the “American oil hegemony”[15] and Paul Kennedy’s discussion about the “British coal hegemony”[16] indicate, the prerequisite condition of significant structural changes in the international system is an energy power revolution based on the emergence of next-generation energy-led countries. Many of the world’s major oil producing regions are also locations of geopolitical tension, and possibilities exist of unexpected supply disruptions. Instability in producing countries is the biggest challenge we face, and it adds a significant premium to world oil prices. Palestine, Iraq and Iran will push the geopolitical tension in the Middle East, the world’s largest oil producer. Darfur of Sudan, democratic transition in Congo and Zimbabwe, all of these pose potential dangers to African oil production. Because of such geographic imbalance, many actors are increasingly competing over the control of energy resources. In 1978, the major international oil companies dominated more than 70% of the production of oil and gas, but now it decreased to only 20%. Currently, the state-owned or state-controlled oil company control nearly 3/4 of the conventional proved oil and gas reserves of the world. This has fundamentally changed the relations between state-owned enterprises and private corporations, caused a lot of consequences. Meanwhile, it also provoked a battle over the Arctic, which remains the last unoccupied oil and gas territory of the world. The two energy crises in the 1970s have brought home to all countries the strategic importance of energy and the great impact of not having a stable supply of energy on the economy. With the end of the Cold War, the role of the military in national security has declined relatively, but the status of economic and energy security has steadily risen, instead of declining.[17]

According to Figure 2 (the Change of Oil Import Geography in the Middle East and Africa), from a geo-strategic perspective, US worries about China’s rapidly increasing oil demands will certainly lead to the redrawing of the world’s oil political map in the coming decades. China is engaged in a search for oil that has it settle deals with Iran, Sudan, Burma, and other sources the US considers unsavory. China has already become the most important trading partner of the Gulf countries at present. In 2012, with an increase of 15.9% the bilateral trade volume between China and the Gulf Arab countries reached 155.03 billion dollars which accounted for almost 70% of the total trade between China and Arab countries.[18] Saudi Arabia is the largest trading partner of China in West Asia. In 2012, the bilateral trade volume reached 73.27 billion U.S. dollars with an increase of 13.9%.[19]

II. China’s Energy Security

The energy security problems China has to deal with are as follows. First of all, the oil consumption is heavily relying on import and it is reported that the degree of dependency has reach 58% in 2012. Secondly, the import of oil is excessively dependent on the Middle East. Thirdly, the import lanes of oil heavily focus on the Strait of Malacca. Fourth, China is compelled to pay extra costs for oil import because of the “Asia Premium”. For China’s external energy security, the Gulf region and energy transport are two issues to which should be attached the greatest importance. China is the newest player on the world energy market. Major Chinese oil companies started international operations in the 1990s and have made impressive progress. Peaceful energy development and international energy cooperation are the international dimensions of China’s energy policy. As a rising power on the peaceful development road, China’s energy strategy features mutual benefits and policy of building a harmonious world. China has taken an active part in energy cooperation with other countries on the basis of mutual benefit to ensure the stability of the regional and global energy markets. “The core of China’s energy strategy is to give a high priority to conservation, rely mainly on domestic supply, develop diverse energy resources, protect the environment, step up international cooperation of mutual benefit and ensure the stable supply of economical and clean energies.”[20] China also developed a new energy security concept that calls for mutually beneficial cooperation, diversified forms of development and common energy security through coordination.

2.1. China and the Gulf Region

As early as the 1970s, OPEC began to exert an extraordinary influence on the international energy system. From the international economics perspective, OPEC is an energy cartel created to control or monopoly the price and supply. OPEC can make the collective decision to limit or enlarge their oil production in order to monopoly the oil market and compete with non-OPEC oil producing states. In the long run, the influence of OPEC in international energy system is expected to rise. According to an IEA report, energy supply is increasingly dominated by a small number of major producers where oil resources are concentrated. OPEC’s share of global supply will grow to 48% by 2030 from 40% now and 42% in 2015.[21] In December 2006, OPEC’s Secretary-General announced that Sudan and Angola would become new members of OPEC which would significantly increase the world oil market share of OPEC. More than half of the crude oil imported by China is from the Middle East. In recent years, China has had fruitful cooperation with Gulf countries in energy and in other areas and has started the energy dialogue mechanism with them. Negotiations for a free trade agreement are underway. China has secured big energy projects in Saudi Arabia and Iran. There is a good prospect for energy cooperation between China and the Gulf region. Thanks to Saudi Arabia’s strong support, OPEC and China have entered into official exchange relations. The first China–OPEC Energy Roundtable was held in April 2006. Since the Iranian nuclear issue became a hotspot, China’s energy relations with Iran have become the target of criticism. Some scholars argue that China’s quest for energy might make China take sides with Iran, which might dilute the international efforts pressuring for Iran’s compliance. Such arguments are actually simplified judgments. China’s energy connections with Iran have been growing stronger in the last decade, but they are mostly embodied in the bilateral trade in the energy sector. Since China became a net importer of oil in the 1990s, its import from Iran stayed at the level of 10-15 percent of total imports. What should be especially mentioned is that beyond trade, China’s cooperation with Iran is modest. China signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Iran on energy cooperation in October 2004, which included the joint development of the Yadavaran oil field, which was thought to have a reserve of 17 billion barrels, and China’s import of gas from Iran.

2.2 China and Central Asia

Central Asian states, rich in oil and gas resources, are close neighbors of China. Their importance inworld energy politics is reflected not only in being the new sources of energy supply in the world, but also in their important role in the regional energy linkage. China has continued to strengthen energy cooperation within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). China and India, an SCO observer state, have gradually become the largest oil-consuming countries within the SCO, while Iran, Russia and Central Asian countries are the most important OPEC members. The 11 participating countries at the SCO conference should discuss how to improve the efficiency of cooperation and to put in place some kind of regional energy mechanism (or regional consultations and arrangements for consumption, production and transportation, etc.), which will have an important impact on the future international energy system. To enhance energy cooperation within the framework of the SCO is not only conducive to materializing China’s energy diversification strategy, it may also facilitate Sino–Russian energy cooperation. Once the Sino–Kazakh oil pipeline project is completed, Central Asian countries will increase their oil exports to China. Russia will also inject oil into this pipeline so as to make up for the inadequate rail capacity to ship its energy exports to China. Work is being done to extend this pipeline to Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries. The Sino–Kazakh oil pipeline will also be linked with the Russia-Iran oil pipelines. By then, there will be an oil shipping network conducive to multilateral energy cooperation within the framework of the SCO. In addition, the gas pipelines from Turkmenistan to China under the plan will run through Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which may make it easy to link with the natural gas pipelines between China and Central Asian countries and between China and Russia.

2.3 Transport-line and Energy Security

Energy is increasingly related to transport corridors. As the distribution of oil reserves does not correspond with that of oil consumption, most of the oil supply is transported through land or sea routes. Maritime oil tanker transport accounts for about 60% of the world oil shipments, while the rest 40% must be transported by the tubing or other land systems. The maritime oil transportation has a great effect upon the economic growth in Northeast and Southeast Asia. The Strait of Malacca is the second largest chokepoint in global oil transportation and trade shipments through this region accounts for about 30 percent of international trade. Yet this area has been plagued by piracy for a long time. After 9/11, in the face of a global anti-terrorism campaign, terrorists in Southeast Asia have moved their arena to the strategic sea lanes and chokepoints. Furthermore, the line between current terrorism and organized crime is getting dimmer, thus, it leaves a greater effect on the sea lanes security in the region of Malacca. The tankers shipping to Japan, China or the U.S. West Coast tankers must be made through the Straits of Malacca and Singapore Straits. About 2 million barrels of oil is transported to the East Asian countries through these two straits. And the tankers shipping to Europe and the U.S. East Coast are via the Suez Canal or the Cape of Good Hope.

There are mainly three imports of oil shipping lanes in China: (1) the Middle East routes, the Persian Gulf ─ the Strait of Hormuz Strait of Malacca ─ Taiwan Strait ─ China; (2) the African routes: North Africa ─ Mediterranean ─ Gibraltar strait ─ Cape Horn ─ the Strait of Malacca ─ Taiwan Strait ─ China; (3) Southeast Asia routes: the Strait of Malacca ─ the Taiwan Strait ─ China. That is to say, except the Pacific shipping lanes that China imports from South America countries such as Venezuela, China’s oil transportation from other directions must go through the Strait of Malacca. The Strait of Malacca as a shipping lane accounts for about 85% of China’s total oil imports, so the Strait of Malacca is the choke points of China’s oil imports. The actions that China actively built relationships with global oil producers to ensure its energy supply had caused the attention of the U.S. and Japan, increasing concerns about China’s proactive diplomacy and growing demand for energy could lead to conflict with America and Japan in the future.

III. China-US Energy Ties

At present, China’s dependency of coal import is 14.6%, and of oil import above 65.7%. As the two large consumers and importers in energy resources, China and the U.S. share common needs and foundation in energy, especially for oil and gas fields. Being the first two largest oil consuming countries, the U.S. and China should be entitled under the new energy concept toward energy issues to strengthen dialogue, communication and coordination, to build a constructive relationship full of healthy competition and strategic partnership. Former U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary Shriver pointed out that the growth of the U.S. and China’s oil demand may lead to two very different prospects: one may be a fierce competition for oil supply; the other is an increased mutual cooperation not only in oil but in all aspects. With occurrence of the U.S. shale gas revolution, the U.S.’s dependence on foreign energy is declining while the cooperation factors of the Sino-US energy relations are rising.

3.1 Position Change of China and the US in Energy Geography and Cooperation Foundation

Particularly, the oil demands and import continues to drop and the production is increasing in the U.S. while in China, the demands and import of oil has increased dramatically compared with the slight fall of production. Therefore, the energy relation between China and the U.S. has changed and the latter has increasingly become an important global producer which will lead to the reducing of competition between the two countries in the field of oil demands. The energy security problems China has to deal with are as follows. First of all, the oil consumption is heavily relying on import and it is reported that the degree of dependency has reach 58% in 2012. Secondly, the import of oil is excessively dependent on the Middle East. Thirdly, the import lanes of oil heavily focus on the Strait of Malacca. Fourth, China is compelled to pay extra costs for oil import because of the “Asia Premium”. By comparison, the degree of dependence of oil imports of the U.S. is increasing by years promoted by the shale gas revolution while its oil import from the Middle East is falling. The U.S companies try to expand oil exploration and controlling of non-OPEC countries especially for surrounding countries. The Middle East turns to actively develop energy relations with China influenced by the decrease of import from the U.S. As the largest trading partner of Saudi Arabia, China has surpassed the U.S.

People from the US government and academia choose to believe that the U.S. and China share common interests when facing challenges in the energy sector including free supply of oil as well as alleviation of environmental damages. Concretely speaking, there exists 3 opportunities for US-China cooperation. With regard to geopolitics of energy, both countries could jointly safeguard security and stability in the areas where oil is produced or transported; with respect to the orderly operation of international energy market, both countries could also join hands to arrange guidance to the oil price; energy technology promotion is the last but not the least field which both countries could establish partnership and collaborate to develop oil exploitation technologies, improve energy efficiency and solve the environmental problems caused by energy use. Economically, with rapid growth of China’s economy, the U.S. and China become more and more interdependent in economy as well as trade, which have made both countries enjoy great benefit. Since the US have become China’s second largest trade partner while China ranks third among US trade partners and also the fastest-growing export destination for US goods and services, at the same time, US is China’s top investor and vice versa, the US and China are closely bound up on international energy governance. Both countries could gain nothing if they collide for oil leading to the chaos of international energy system. China’s demand for energy stimulates economic growth in developing countries and impacts global oil market. For this reason, the U.S. and China should exert their influence on those oil-producing countries rather than compete with each other for oil.

The US and China share common interests in maintaining the stability of oil-producing countries. It is noteworthy that ensuring ample supply of oil on the global market has been put in one of several US energy policy priorities which could meet the needs of big oil consumers in the world. This provides spacious room for China-US cooperation on international energy policy and guaranteeing the steady supply of oil, which is the biggest converging point of their interests with respect to energy issues. The U.S. and China could make the global energy market function in a stable way by coordinating their energy policies within multilateral frameworks as well as taking concerted actions with other countries. The Middle Eastern countries are China’s most important energy suppliers. In view of US real dominance on the Middle East energy, China, when expanding its cooperation with oil-producing countries in that area, has to try to avoid conflicts with the US. Both the U.S. and China play vital roles in the energy transportation on the sea, hoping to build up safe and secure lanes for marine transport. Therefore, there are a lot of needs for both countries to launching initiatives on anti-terrorism or anti-piracy on the international sea lanes.

The positioning of the Sino-U.S. relationship on energy is emerging with positive changes. The US will be the biggest energy-producing country and China will be the biggest energy consumer in the future, as the global energy production center shifts to the US. By 2020, the Sino-US energy relationship will change gradually with the falling demand and increasing production and export of US energy and the increasing demand and import and the falling production on the side of China. The USA and China will be mutual partners but not competitors on energy. Second, it is in the US interest to maintain the global energy market. The Obama administration and his predecessors have different energy policies to China. Obama welcomed China to invest in North America. From 2011, China’s energy investment in North America has been increasing greatly. Especially the Foreign Investment Review Board of the US approved the China National Offshore Oil Corporation buying Nixon of Canada for 12 billion, which indicated that US wariness of investment from China is decreasing. The US has technology advantage in natural gas, nuclear power, coal and renewable energy, which means that China is interdependent with the US.[22]

Thus, the energy relation between China and the U.S. needs to be repositioned. With the global energy production axis shifting to the North America, the U.S. will become the largest energy production country in the future while China will be the largest consumer. Under this circumstance, Sino-US cooperation in the energy field has been changed from competitors to mutual benefit partners. As recently, the acquisition of Nixon Company of Canada by the China National Off shore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) won the approval of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., which means the U.S. has reduced wariness of China’s energy investment and the Sino-US energy relation is pushed forward in a benign and complementary direction. The driving force of the energy strategy of the U.S. is technological innovation. The transition from a country comparatively lack of gas and oil to a large energy export country in the future is closely related to its innovation in energy technology. China may improve technology and enhance capacity of overseas development by cooperating with the U.S.

3.2 Gulf Region

In the Middle East, China and the United State share common interests which include maintaining security and stability of oil production and transportation in geopolitics, guiding oil price by cooperation in orderly operation of international energy market and also for energy technology, both China and the U.S. may conduct cooperation in oil exploration, energy conservation and efficiency as well as energy related environmental protection. The Middle East is a crucial source of oil import for China and since the politics and economy of this area is under the actual control of the U.S., China must handle relations with the U.S. properly in order to expand cooperation with Middle Eastern oil-producing countries. Particularly, the trilateral relations of China, the Middle East and the US are the key elements measuring the Sino-US energy relationship. The major consuming countries and importing countries in the energy sector can find their common interest, especially to oil of energy sector in the Asia-Pacific. China and the U.S. can avoid deteriorating their political relationship but cooperate in the energy and trade sectors to promote the stability and development on the global energy market. The U.S. has advantage in natural gas, nuclear energy, coal and renewable energy, and China’s reliance on the U.S. for energy is growing, so it is important for China to cooperate with the U.S. but not conflict with it. The Middle East has actively developed the energy relationship with China. Now China is the most important trade partner to Gulf countries. On the one hand, China and the US have common interests in maintaining the security of Middle East from the perspective of energy geopolitics. On the other hand, it is China’s chief strategic direction to ensure the ample supply from the Middle East. China has to rely on sea power to maintain the security of increasing oil and gas import, and also increase investment in gas and oil in the world, as the US army has controlled the import value of China’s oil and gas. But all this will raise US concerns about the cooperation between China and the Middle East as the challenge to US sea power. Specifically, when the US does not need to import from the Middle East and is energy independent as a result of the “Energy Revolution”, it will be able to “change” the Middle East. And this will threat China’s energy security.

3.3 Energy Transport