- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- The Contexts of and Roads towards t...

- Three Features in China’s Diplomati...

- The Green Ladder & the Energy Leade...

- Building a more equitable, secure f...

- Lu Chuanying interviewed by SCMP on...

- If America exits the Paris Accord, ...

- The Dream of the 21st Century Calip...

- How 1% Could Derail the Paris Clima...

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Evolution of the Global Climate Gov...

- The Energy-Water-Food Nexus and I...

- Sino-Africa Relationship: Moving to...

- The Energy-Water-Food Nexus and Its...

- Arctic Shipping and China’s Shippin...

- China-India Energy Policy in the Mi...

- Comparison and Analysis of CO2 Emis...

- China’s Role in the Transition to A...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- China's Global Strategy(2013-2023)

- Co-exploring and Co-evolving:Constr...

- 2013 Annual report

- The Future of U.S.-China Relations ...

- “The Middle East at the Strategic C...

- 2014 Annual report

- Rebalancing Global Economic Governa...

- Exploring Avenues for China-U.S. Co...

- A CIVIL PERSPECTIVE ON CHINA'S AID ...

Revival of the “Silk Road” is considered to be a new global integration project between China and Central and South Asia, Europe and the Middle East. The global economic crisis and domestic social problems have made China’s traditional export-driven economic model less effective. Evidently, China needs to secure existing export markets and diversify its transport network, especially given the instability in the sea lanes in Asia’s South and South-East.

At the same time, China needs to find new export markets including investment ones, as well as to narrow development gaps between the well-developed coastal areas and the less-developed inland parts of the country. It is expected that implementation of the New Silk Road project will cause necessary transformation.

The New Silk Road concept is associated with a “new Silk Road economic belt” which indicates stronger economic relations between China, Central Asia and Europe with a special focus on trade. Moreover, jointly building the New Silk Road Economic Belt will improve[①]:

- policy communication, which will help to expand economic cooperation;

- road connections with the idea to establish a great transport corridor from the Pacific to the Baltic Sea, which stimulates the building of a network of transport connections between Eastern, Western and Southern Asia;

- elimination of trade barriers and reduction of trade and investment expenses;

- people-to-people relations.

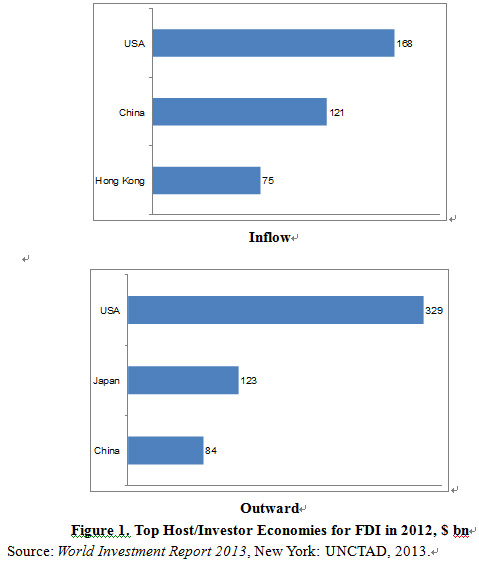

Clearly, the main role in the concept implementation is attributed to China, especially in investment, and it is thus necessary to examine the new wave of investment expansion. The global rankings of the largest recipients of FDI reflect the changing patterns of investment flows: 9 of the 20 largest recipients are developing countries. And China is considered to be among the main (among the TOP three) world recipients/importers and investors/exporters of the FDI (figure 1).[②]

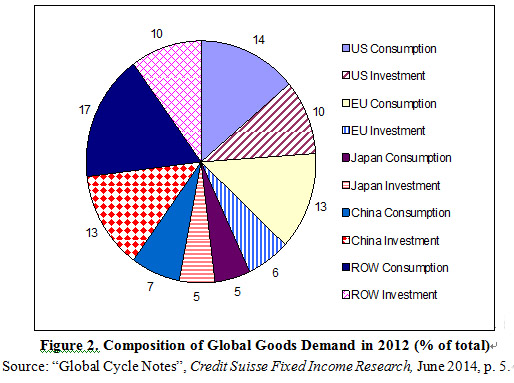

Moreover, in recent years Chinese investment, U.S. and EU goods consumption, as well as “rest of the world” consumption, have been the major drivers of global goods demand (figure 2). These are the reasons for the lasting growth of global manufacturing.[③]

While Asian countries have become the main actors of the New Silk Road, Central and Western Europe is considered to be the ultimate point of the project. At the same time, more efficient ways for Chinese businesses in the EU direction may not be trade flows but investment expansion in countries bordering the EU.

Particularly, the inclusion of Ukraine into the project might introduce new content, create additional project integration possibilities, significantly change the structure of economic integration in Eastern Europe and start new investment and trade directions of development with wide benefits for both China and Ukraine.

It is clear that Ukraine is far away from China and there are substantial differences in the economic nature between both countries. However, some similarities of macroeconomic dynamics for both countries provide useful insights for our consideration and better understanding of potential benefits.

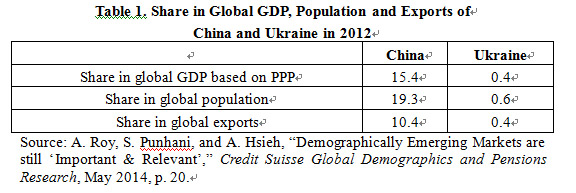

II. “Similarities” between Chinese and Ukrainian economic environments

China and Ukraine are among emerging markets and China’s economy is much larger than Ukraine’s. The share in global GDP based on PPP is 15.4% for China, while 0.4% for Ukraine, the share in global population – 19.3% for China and 0.6% for Ukraine, the share in global exports stood at 0.4% in Ukraine to 10.4% in China in 2012 (table 1).[④] Thus, Ukraine is actually invisible in the global economy but even such a small country can expand opportunities and prospects for large China when entering the European markets.

China’s total volume of foreign trade in 2012 reached USD 3.9 trln, which ranked the 2nd place in the world,[⑤] but China-Ukraine trade took only around 0.3% of China’s total trade. In the aspect of foreign investment, China’s direct foreign investment volume in 2012 ranked the 3rd place in the world, but the share of Ukraine is close to zero (only 0,02% of China’s total FDI). With the deepening of economic globalization and the expansion of global value chains, huge development potential still remains in China’s economy, including investment in Ukraine.

As far as China is much larger than Ukraine, why do we argue that Ukraine is a country for China’s investment expansion? Perhaps surprising, but the economic environment of Ukraine can be a “complementary” one for China.

If we consider some of the indicators that measure institutional factors, we can observe that in general, China is ranked better than Ukraine. In particular:

•World Bank’s Ease of doing business index ranks economies so that a high ranking means that the regulatory environment is conducive to business operation. Here China ranks a little higher than Ukraine (96 vs 112, accordingly);

•at the same time, UNDP’s Human Development Index measures development by combining indicators of life expectancy, educational attainment and income into a composite index and serves as a frame of reference for both social and economic development. According to this rating, Ukraine ranks better than China (78 vs 101);

•World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index is a comprehensive tool that measures microeconomic and macroeconomic foundations of national competitiveness, which are defined as the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country.[⑥] As shown, institutional environment in China is much better than in Ukraine (figure 3). But Ukraine receives rather high scores in such pillars as “Higher education and training” and “Technological readiness”, which also means that Ukrainians are educated, trained and are ready to produce high value added products.

Evidently, institutional factors need to be improved in order to foster economic and financial market development in Ukraine and to make it closer to China’s.

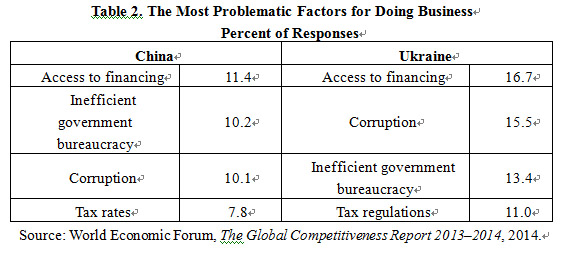

At the same time, problematic spheres for business are similar in China and Ukraine (table 2), according to the ratings of the most problematic factors for doing business.[⑦]

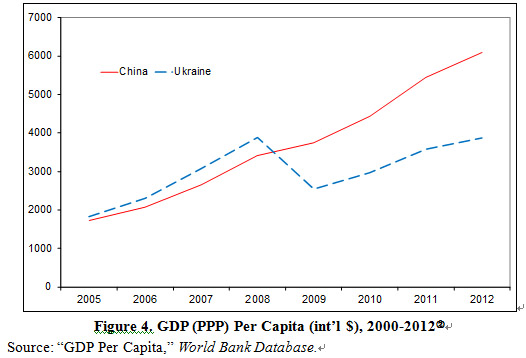

Ukraine lost a lot during the last economic crisis. While in the mid 2000s Ukraine demonstrated rather positive dynamics, in 2009-2012 the growth was very slow and Ukraine declined in wellbeing (figure 4).[⑧]

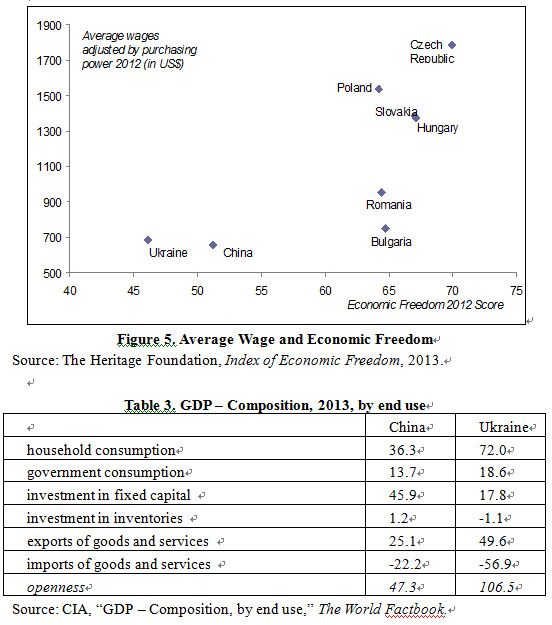

Also, Ukraine stands behind Central and East European countries in the level of Economic Freedom. At the same time, Ukraine demonstrates some competitive advantages – particularly, labor cost (associated with average wage) in Ukraine is the smallest among mentioned countries (figure 5). This means that in the case of institution improvement, investment attractiveness of Ukraine will grow considerably and provide higher benefits (due to low labor cost of well-educated and trained employees).

The saving ratio in China is around 50%, which restrictively affects the development of domestic markets. In Ukraine, however, like in all European countries, excessive consumption spending, investment deficit and even loss of investment potential is observed (table 3).[⑨] In such situation competitive advantages of China need to be transformed into “efficiency advantages” based on higher capital mobility to form a new competitive advantage.

Recently the situation that cheap resources and labor forces serve as important competitive advantages supporting the development of export trade in China has changed. Due to the long-term rise of labor costs and wellbeing of households it becomes difficult to maintain the traditional competitiveness based on high investment and low consumption.

III. Advantages of Free Market between the EU and Ukraine: New Opportunities for China and Ukraine

The driving forces of economic globalization are undergoing significant changes. For the past five years, since the peak of the global financial crisis, the world economic recovery has yet to be fundamentally stabilized. Hence, it has become increasingly important and urgent to enhance China’s economy as a source of world growth through speeding up the formation of new competitive advantages in participating in and leading international economic cooperation.[⑩] This is the core element for improving the international competitiveness of Chinese products and services and the significant support for transformation.[11]

Thus, in terms of our consideration, direct economic links between China and Central and East European countries are urgent and important. In November 2013 China’s leaders at the 2nd China-CEE16 summit[12] presented new proposals for enhancing relations with the region. Among those proposals there was a suggestion for closer cooperation in the transport and infrastructure sectors, which may facilitate economic cooperation. That means that China’s “opening to the West” and reinvigoration of its Western Development Policy creates a window of opportunity not only for CEE countries[13] but also for the East European ones as a whole.

Particularly for Ukraine, as far as new opportunities and chances for the country appear, the growth of investor interests due to huge changes in political situation, wide cooperation with the IMF, World Bank and other institutional investors, as well as the complete implementation of the Association Agreement between the EU and Ukraine,[14] are expected.

Since 2008 the EU and Ukraine have negotiated the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA). The free trade area between the EU and Ukraine is designed to deepen Ukraine’s access to the European market and to encourage further European investment in Ukraine. Let us emphasize that the EU is among Ukraine’s most important economic and trade partners and accounts for about one third of Ukraine’s external trade.[15] At the same time the EU is the largest investor in Ukraine’s economy. Thus the DCFTA has rather strong potential.

It is reasonable to underline that the DCFTA is a part of the Association Agreement which replaces the previous Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between the EU and Ukraine. Following the unprecedented situation in Ukraine, in March 2014 the EU and Ukraine signed the political provisions of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. At the same time, the implementation of the remaining provisions, including the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), is being expected later, in 2015.

Without waiting for the entry into force of the Association Agreement’s provisions of the DCFTA, the EU decided to start the unilateral elimination of the EU’s customs duties on goods originating in Ukraine. The regulation on Autonomous Trade Measures to Ukraine was adopted and unilateral reduction of customs duties entered into force at the end of April 2014. This means that about 98% of the customs duties that Ukrainian iron, steel and farm producers and exporters pay at the EU borders have been removed. This unilateral measure will boost Ukraine’s struggling economy by saving its manufacturers and exporters €487 million a year. At the same time, thanks to such unilateral measures, Ukrainian producers and exporters will improve their possibilities to enter the EU markets as a whole.

The future DCFTA between the EU and Ukraine will cover all trade-related areas (including services, investments, intellectual property rights, customs, public procurement, energy-related issues, competition, etc.) and also tackle the so-called “beyond the border” obstacles through deep regulatory approximation with trade-related EU sectors. In such situation foreign investments can produce high profits and benefits for investors.

A number of Ukrainian politicians insist on urgent entering into force of the economic provisions (DCFTA) of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, arguing that the fast foreign investment expansion will happen immediately after the Agreement is adopted. Simultaneously, some renowned international companies specialized in the automotive industry declared that they would begin construction of lines and plants in Western parts of Ukraine immediately after the starting of the DCFTA.[16]

In conclusion, current Ukraine’s investment gap and the coming free trade agreement between Ukraine and the EU create great development potential and economic benefits for foreign investment in Ukraine, including China’s. The above-mentioned institutional “similarities” can help Chinese investors to adapt quickly to Ukrainian business climate.

Source of documents: Global Review

more details:

[①] Szczudlik-Tatar J., “China’s New Silk Road Diplomacy,” PISM Policy Paper, No. 34 (82), December 2013.

[②] UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2013, Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development, New York: UNCTAD, 2013, http://unctad.org/en/publicationslibrary/wir2013_ en.pdf.

[③] “Global Cycle Notes”, Credit Suisse Fixed Income Research, June 2014.

[④] A. Roy, S. Punhani, and A. Hsieh, “Demographically Emerging Markets are still ‘Important & Relevant’,” Credit Suisse Global Demographics and Pensions Research, May 2014, p. 20.

[⑤] Gao Hucheng, “Promoting the All-Round Enhancement of China′s Open Economy,” Qiushi, Issue 2, 2014, pp. 110-117.

[⑥] World Economic Forum, The Global Competitiveness Report 2013–2014, 2014, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2013-14.pdf.

[⑦] Ibid.

[⑧] GDP Per Capita in Current USD in 2013 Estimated in China – $ 9181, Ukraine – $ 6747.

[⑨] CIA, “GDP – Composition, by end use,” The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/ publications/the-world-factbook/docs/notesanddefs.html?fieldkey=2259&alphaletter=G&term=GDP - composition, by end use.

[⑩] Some global integration projects are under formation now. In particular, USA and EU have carried out the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and other “high-level” negotiations concerning free trade zones, which have a far-reaching impact on international economic and trade environment and created opportunities for China to improve its position in global value chains.

[11] Gao Hucheng, “Promoting the All-Round Enhancement of China′s Open Economy”.

[12] The CEE16 includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Croatia, Montenegro, Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Hungary.

[13] Szczudlik, “China’s New Silk Road Diplomacy”.

[14] Association agreements are the most advanced type of international treaties that the EU may conclude with third countries – the countries with which the EU is ready to develop strong long-term alliances based on mutual trust and respect for common values.

[15] Ukraine’s primary exports to the EU are iron, steel, mining products, agricultural products, and machinery. EU exports to Ukraine are dominated by machinery and transport equipment, chemicals, and manufactured goods.

[16] In particular, the Japanese company, “Fujikura,” announced plans to create more than 3,000 jobs at its new plant in the Lviv-city industrial park.